But this kind of high regard for Jesus is by no means universal. Even in Scripture, we find people who reacted to Jesus with hostility, and chief among these people are the scribes and Pharisees. We read in Luke 20 that the scribes and the chief priests sought to have Jesus arrested. In John 5, we are told that they wanted to kill Him, and in chapters 8 and 10, they tried to stone Him.

When we read these accounts in Scripture, we are prompted to ask, Why did these people speak the way they did and feel the way they did with such hostility toward Jesus? It’s difficult to provide a complete answer as to why they were motivated in this way, but here are three reasons why the religious authorities hated Jesus so much.

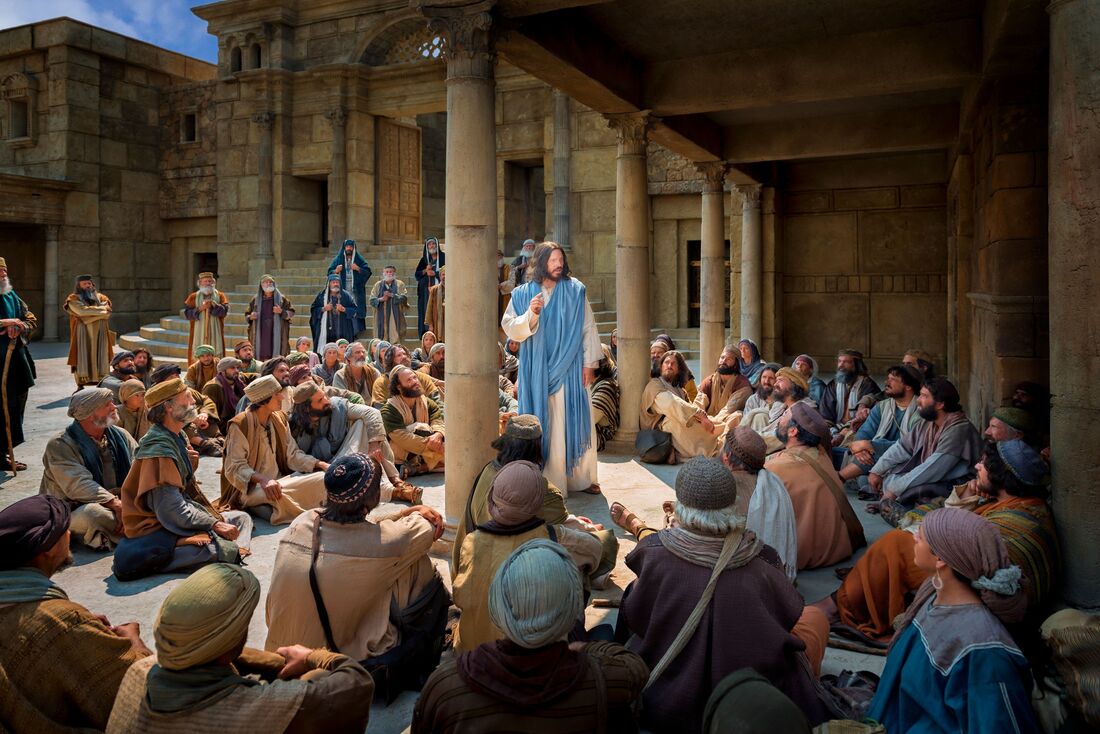

The first is this: they were jealous of Him. Why would they be jealous of the Son of God? Everywhere Jesus went, He attracted huge throngs, multitudes, crowds pressing around to listen to His every word, watching His every move. He was profoundly popular among the people, whereas the rulers of the Jews laid heavy burdens on their people, and they approached the masses, the people of the earth, with something like a spirit of disdain and scorn. While they wouldn’t think of having dinner with a tax collector, Jesus freely associated with people whom the Pharisees considered “rabble.”

The people loved Jesus, and they received Him gladly, but what they felt from the Pharisees was judgment. The only thing the Pharisees looked at was the people’s sin, and so they had a certain contempt for the common people. They saw Jesus associating with the common people and saw them cheering Him, loving Him. They couldn’t stand it because they were envious and suspicious of His popularity.

The second reason why they hated Him was because He exposed them. Before Jesus came, it was the Pharisees particularly, as well as the Sadducees and scribes, who set the moral standard for the community. They sat in the highest places in the synagogue. They were the ones who were most honored and celebrated for their virtue, but their virtue, as Jesus taught repeatedly, was a pretense. It was external. He said: “You’re like dead men’s tombs, whitewashed sepulchers that are painted without blemish on the surface but inside are filled with dead men’s bones. You clean the outside of the platter, but the other side, the inner side, is filthy. You do everything possible to hide that impurity, that grime, and that filthiness from public view. You pretend to be righteous, and you major in that pretense of being righteous.”

The Pharisees started in the intertestamental period as a group who were upset because the people were abandoning the purity of the covenant that they had made with God and were being lax in their morality and in their obedience to the commandments of God. So the Pharisees sought to draw together and draw apart from the masses and to set a moral example. These were the conservatives of the day. They had a high system of honor and virtue, and they committed themselves to obeying God. In fact, one sect among the Pharisees believed that if they could keep every law that God gave in the Old Testament for just twenty-four hours, then that would prompt God to send the Messiah to Israel.

But a lot of things had happened between the day of the formation of the Pharisees and the time of Jesus’ incarnation, when they masqueraded as devotees of righteousness and obedience. In a word, they were counterfeit. They were fake. And nothing reveals a counterfeit like the presence of the genuine. When Jesus walked this earth, true righteousness and holiness was manifested by Him before the eyes of the people. It didn’t take exceptional brilliance to discern the difference between the real and the counterfeit. So the Pharisees were exposed, and because they were exposed by the true and authentic holiness of Christ, they hated Him, and they couldn’t wait to get rid of Him.

There is a common idea out there that God must grade on a curve. Grading on a curve happens when an instructor gives an exam and everyone flunks it. It must therefore be a bad or unfair exam, or the teacher has failed in teaching because the students have failed to learn. The instructor then grades on a curve, so that an F might be counted as a C and a C as an A, and so on. There’s a formula for doing that.

But every once in a while, you have someone who breaks the curve, meaning that everyone else failed the test but this student scores very high. This messes up the formula, which means that most students don’t like people who break the curve. Curve breakers make the rest of us look bad.

The bad news is God doesn’t grade on a curve. A lot of people think He will, but there is no curve. All people will be judged according to His perfect standard of righteousness. There is no sliding scale.

The good news, however, is that Jesus broke the curve. While we all fall short, He achieved a perfect record of righteousness. And He did so for us. While this is a source of rejoicing for those who have placed their faith in Christ, it moved the Pharisees to hate Him because He exposed their phony righteousness for what it was.

The third reason I think that they hated Him is because they were afraid—not so much of what He would do to them in His wrath but of the consequences of welcoming Him into their midst. Why were they afraid? Look at the history of Israel. In almost every generation going back to Abraham, the Israelites lived under the domination and oppression of a foreign nation. You’ve heard of the Pax Romana; there’s also the Pax Israeliana. The Pax Israeliana, or the peace of Israel, was always extremely short-lived. Almost always, the people were a conquered people, a people who lived under the oppression and the tyranny of their enemies. In the case of the first-century Jews, the oppressor was Rome.

Throughout Jewish history, there had always been those who were committed to revolution, who wanted to throw off the yoke of the foreigners who held them captive. You’ll see one revolt after another in the history of Israel, and one revolt after another being quashed by the power of the enemy. There were people—at least two, probably more—among Jesus’ disciples who were called Zealots.

Those who were in positions of power and authority, as the Pharisees and Sadducees were, feared losing their power and authority. The Jewish leaders feared the consequences of a revolt against Rome. That’s on almost every page of the New Testament. They feared the Romans. They feared that Jesus somehow would lead an insurrection, cause another uprising, and consequently bring a bloodbath, and so they sought to remove Him before He caused them trouble.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed