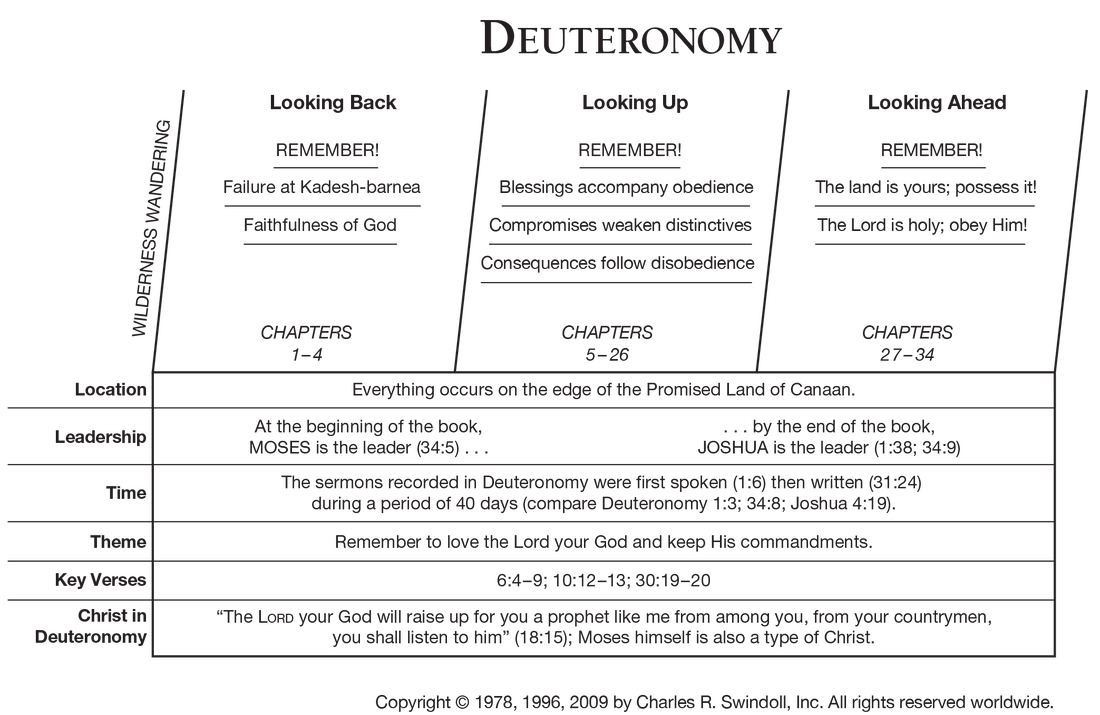

Deuteronomy, which means “second law,” was originally given as a sort of pep talk for the people of Israel on the eve of their entering the Promised Land. All the generation who left Egypt in Exodus 13 and rebelled in Numbers 13 has now died, and the children who came of age in the wilderness are the new generation. In a series of four speeches or sermons, Moses repackages the previous books (citing nearly 50 separate chapters of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers) into lessons for the new generation.

In his first speech (Deuteronomy 1-4), Moses combines warnings against breaking faith and encouragements to trust God. He uses both history, recalling events from Numbers, and commentary, reflecting on the uniqueness of the Exodus. God gave them laws wiser than those of any nation (4:8). He was nearer to them than the (false) god of any other nation (4:7). They had heard God “speaking out of the midst of the fire” and lived (4:33). God had taken “a nation for himself from the midst of another nation, by trials, by signs, by wonders, and by war, by a mighty hand and an outstretched arm, and by great deeds of terror,” which no other god had ever attempted (4:34). The inevitable conclusion of these bulletproof arguments is that “the Lord is God in heaven above and on the earth beneath; there is no other. Therefore you shall keep his statutes …” (4:39-40).

The second speech (in chapters 5-26) is a commentary on the law. Moses restates the 10 Commandments (5), expands on the regulations for heart worship (6-11), reiterates the regulations for ceremonial worship (12-17), gives regulations for officials (18-19) and society (19-25), and concludes with a liturgy for firstfruits and tithes (26). These rules were to remind the people about their responsibilities toward God and toward each other, so that they would be a people holy to the Lord, and not become like the wicked nations God would drive out before them.

Expanding for a moment on this section, Deuteronomy 6-11 are some of the most important chapters in the Old Testament. Here we find the “most important” commandment that Jesus quotes, “Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God, the Lord is one. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might” (6:4-5, Mark 10:29-30, see Deut. 11:1). Here is the command to “teach them [these commands] diligently to your children (6:7, see 11:19). Here is the command to “circumcise therefore the foreskin of your heart,” (10:16), indicating that the religion that pleases God is internal, not merely external. Here is the warning, “take care lest you forget the Lord your God … when you have eaten and are full” (8:11ff). Here, too, we find God’s sovereign grace overriding the Israelites stubborn rebellion, “know, therefore, that the Lord your God is not giving you this good land to possess because of your righteousness, for you are a stubborn people” (9:6), and “you are a people holy to the Lord your God. The Lord your God has chosen you …” (7:6). These chapters are repetitive in their calls to obey the Lord, but only because we need to hear it often; this vital theme can yield endless, sweet meditation.

The third speech (27-28) sets forth the curses and blessings that were consequences of the covenant, which the Israelites were to solemnly recite upon conquering the land. For Moses’ present purposes, the rewards for obedience are really good, and the consequences for disobedience are really bad. For us, who have the full canon, we can see how these promises of God are ominous foreshadowings of the judgments that will eventually overtake Israel. When you’re reading through the kings or the prophets, compare the sins and judgments with these chapters, and it will add another dimension to your perception of God’s justice.

In the fourth speech (29-30), Moses emphasizes the stakes of obedience or disobedience as the people renew the covenant. “I have set before you life and death … Therefore choose life,” he urges (30:19). He clarifies what the people are responsible for (obeying God) and what they aren’t responsible for (playing God). “The secret things belong to the Lord, but the things that are revealed belong to us and to our children forever, that we may do all the words of this law” (29:29). He tells them that the blessings and curses will come upon them, but even then “the Lord your God will restore your fortunes and have mercy on you” (30:3). Even as God makes a covenant with the people, he knows they will fail to keep it, but yet he will remain faithful.

In the final chapters (31-34), 120-year-old Moses prepares to die, settling Joshua as his successor, teaching the Israelites a song, and offering final blessings to the tribes. The triumphant armies of God are about to march into Canaan, but first God commands Moses to teach them a real downer of a song. “Put it in their mouths that this song may be a witness for me against the people of Israel,” the Lord instructs Moses, so that when they rebel and are chastised, “this song shall confront them as a witness (for it will live unforgotten in the mouths of their offspring). For I know what they are inclined to do even today” (31:19,21). The song describes God as a Rock, perfect, just, faithful, upright, and how nevertheless “they have dealt unfaithful with him” (32:4-5).

The Gospel in Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy is the crowning jewel of the five books of Moses, but at first glance it can seem a bit confusing. It seems like the book is sending contradictory signals in different places. The Israelites are God’s special people. They are commanded to obey all his commandments, but also told they will fail. What matters is the heart, but the Israelites also must follow a list of external rules as well. What’s going on? In one sense the book is like a tapestry, creating a richer, more beautiful picture by strands running across each other than would be formed by any of the strands themselves. In another sense, Deuteronomy puts the finishing touches on a building’s foundation; it should not be confused for the building itself — Christ — but it does provide something solid to build from.

We can better understand Deuteronomy’s impact on the rest of Scripture by considering several places where it’s quoted elsewhere. Let’s start with declaration that the commandment “is not too hard for you.” It’s not in heaven, or beyond the sea, “but the word is very near you. It is in your mouth and in your heart, so that you can do it” (30:11-14). Paul quotes these verses with commentary in Romans 10, explaining that these describe the righteousness based on faith. “Because, if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Romans 10:9).

This encouragement must describe the righteousness based in Jesus, because the righteousness based on the law is impossible for us to obtain. Even keeping a single commandment, the one Jesus identifies as most important is impossible. “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might” (6:4-5, Mark 10:29-30). Get alone with your own conscience sometime and consider how you measure up.

From here we turn naturally to consider the consequences of our sin. On this point, what God commands is precisely just. “Fathers shall not be put to death because of their children, nor shall children be put to death because of their fathers. Each one shall be put to death for his own sin” (24:16). The first part of this verse provides a limit for guilt to the individual. If people could die for other people’s sins, who would be left? We read about a just king applying this rule (2 Kings 14:6, 2 Chronicles 25:4), and later prophets reaffirm its justice (Jeremiah 31:30, Ezekiel 18:20). But the prophets also reaffirm the second part of the verse, that “each one shall be put to death for his own sin.” Not everyone commits a crime for which the government will inflict a sentence of capital punishment, but everyone is guilty of “cosmic treason” against God, as R.C. Sproul put it. Our sins have earned us a death sentence.

We see this rebellion against God depicted dramatically in the song of Moses. “Jeshurun [another name for Israel] grew fat, and kicked; you grew fat, stout, and sleek; then he forsook God who made him and scoffed at the Rock of his salvation” (32:15). You can hear echoes of this diagnosis in later prophecies, such as Isaiah 17 or Hosea 13. And again, “they are a crooked and twisted generation” (32:5). Which generation is this referring to? Every generation is evil, says David (Psalm 12:7), Asaph (Psalm 78:8), Jesus (Matthew 12:39, 16:4, 17:17), Peter (Acts 17:17), and Paul (Philippians 2:15). Like an expert prosecutor, the Holy Spirit works throughout all Scripture to convict mankind of sin, leaving no avenue of escape, no fig leaf of excuse.

As Israel acts out their rebellion, the curses of Deuteronomy 28 come upon them — military defeats, famines, plagues, misery, and eventually exile. Yet, even to the exiles, God is “the faithful God who keeps covenant and steadfast love with those who love him and keep his commandments, to a thousand generations, and repays to their face those who hate him, by destroying them” (7:9-10). Both Daniel (Daniel 9:4) and Nehemiah (Nehemiah 1:5) invoke this verse in their prayers of repentance for Israel, pleading with God to remember his covenant. Nehemiah cites Moses explicitly, “If your outcasts are in the uttermost parts of heaven, from there the Lord your God will gather you” (30:4, Nehemiah 1:9). How merciful God is! How many times he withholds his full wrath! How patient he is, waiting for people to repent!

Of course, we no longer live under the Mosaic covenant. No longer are blessings and curses on our land tied to our corporate obedience, because no longer is God’s people confined to a single nation. For us, God’s salvation no longer looks like a return from exile or salvation from raiding bands of Philistines. There were many Old Testament saints, but “all these, though commended through their faith, did not receive what was promised, since God had provided something better for us, that apart from us they should not be made perfect” (Hebrews 11:39-40). We have received what was promised, which is eternal life. That is, freedom from the power and penalty of sin and new life.

We have these great gifts in Jesus Christ, who is also mentioned in Deuteronomy. “If you believed Moses, you would believe me; for he wrote of me” (John 5:46). God told Moses, “I will raise up for them a prophet like you from among their brothers. And I will put my words in his mouth, and he shall speak to them all that I command him. And whoever will not listen to my words that he shall speak in my name, I myself will require it of him” (18:18-19). According to Acts 3:22-23 and 7:37, this is foretelling the coming of Christ. It conforms exactly to what Jesus says about himself, “I have not spoken on my own authority, but the Father who sent me has himself given me a commandment — what to say and what to speak” (John 12:49).

But Jesus is more than a prophet; he is our Savior. He was crucified for us, bearing the punishment our sins deserved. Paul explained, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us’” (Galatians 3:13). The citation is from Deuteronomy 21:23. We were under a curse because we did not do everything written in the law. But Christ became a curse under this other, far more specific provision. He was made a curse for all who believe in him, to cleanse them of their sins.

Now, what God said about Israel is true of us. Moses told Israel, “You are a people holy to the Lord your God. The Lord your God has chosen you to be a people for his treasured possession, out of all the peoples who are on the face of the earth” (7:6). Peter extended that to all God’s people of every nation, “you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light” (1 Peter 2:9).

But Deuteronomy remains of practical use today, even though we aren’t under the old covenant. Throughout the book, Moses exhorts the people to remember what God had done, and so be careful to do what is right. These warnings still apply to our lives, as the author of Hebrews explained. “Beware lest there be among you a man or woman or clan or tribe whose heart is turning away from the Lord our God … Beware lest there be among you a root bearing a poisonous and bitter fruit” (Deuteronomy 29:18, see Hebrews 3:12, 12:15). It warns us not to presume on God’s grace and think, “I shall be safe, though I walk in the stubbornness of my heart” (29:19). God will wipe out the man who thinks that.

Follow the God of Love

Its incredible to see how God had already sown gospel seeds throughout the first five books of the Bible. They point to Jesus so clearly that he said, “if they do not hear Moses and the Prophets, neither will they be convinced if someone should rise from the dead” (Luke 16:31). God has never had to employ his Plan B. The entire Bible fits together as a single masterpiece, and it has pointed to Jesus Christ since the very beginning. There are some who think the Old Testament is less important for Christians, or represents a different, angrier God, or presents the Mosaic law as another way of salvation. I would simply encourage those people to read their Bibles more.

Deuteronomy is stuffed with precious promises, strident exhortations, and beautiful encouragements to follow God and obey him not out of duty, but out of love. It teaches us that our obedience is not conditional upon God fulfilling his promises for us, but rather God’s faithfulness to us inspires us to obey him “as obedient children” (1 Pet. 1:14). God’s word — all of God’s word — gives us what we need to persevere through hard times, to pursue the prize God has set for us, to keep the end in view when we are tempted to quit, and to not lose our heart or our love for God.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed