The Most Diverse Movement in History

I met Senganglu Thaimei (Sengmei to her friends) in New Delhi, India. Born to the Rongmei tribe in the extreme northeast of India, she teaches English literature at Delhi University and writes stories reimaging the tales of her tribe through the eyes of marginalized women. Sengmei is keen to preserve tribal culture, and preservation is necessary. The Naga tribes were reached by Western missionaries in the 19th century. Christianization brought westernization. Today, over 80 percent of the Rongmei are Christian, and tribal traditions are declining.

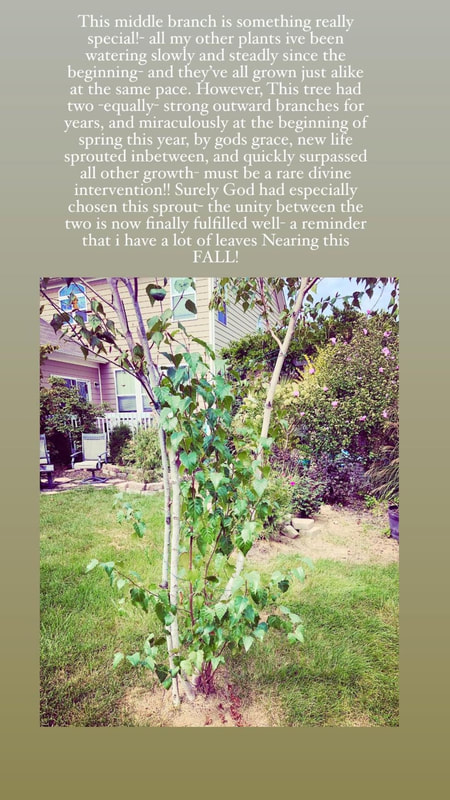

For many, this would be one evidence among many that Christianity is a white, Western religion forcibly exported to other cultures and leaving a trail of cultural destruction in its wake. But the rest of Sengmei’s story complicates the picture. Raised in a nonreligious home, she started following Jesus as a teenager through the witness of a Rongmei friend. Today, she is a passionate Christian and her husband (from a kindred tribe) pastors a multiethnic church.

What’s more, as we discussed the history of her tribe, Sengmei warned me not to give Western missionaries too much credit. Westerners saw only a handful of Naga converts, who then effectively evangelized their tribes. And while Sengmei deplores the ways Western culture was illegitimately packaged with Christianity, she is equally clear about the positive effects of Christianization, especially for tribal women.

I visited India to meet with 12 Christian academics. Ten came from Naga tribes. Between them, they spoke seven indigenous languages. But they spoke with one voice when it came to Christianity. Cultural anthropologist and Naga tribe member Kanato Chophi stated it most starkly: “We must abandon this absurd idea that Christianity is a Western religion.”

Diverse from the Start

Centuries of Western art depicting Jesus as fair-skinned may incline some of us to forget that he was a Middle Eastern Jew who lived under oppressive Roman rule and whose followers were first called “Christians” in Antioch—the ruins of which lie in modern-day Turkey. Christianity did not come from the West.

But nor was it constrained by its culture of origin. Jesus’ life and teachings scandalized his fellow Jews by tearing through their racial and cultural boundaries. For instance, the hero of the Parable of the Good Samaritan came from a hated ethnic group. Jesus commanded his disciples to “go and make disciples of all nations” (Matt. 28:19). They began at once.

In Acts, we see the Spirit enabling the apostles to evangelize people “from every nation under heaven” (Acts 2:5), including those from modern-day Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Egypt (Acts 2:5–11). This move of the Spirit to communicate in the heart-language of those listening is one evidence among many that Christianity is a multicultural and multilingual movement. In fact, the Bible itself is multilingual!

The Old Testament is in Hebrew and the New Testament in Greek. But Jesus’ mother tongue was Aramaic, and the Hebrew Scriptures were mostly accessed by first-century Palestinian Jews via Aramaic translations. We see traces of Jesus’ first language in Mark, when he raises a little girl (Mark 5:41), heals a deaf man (7:34), and cries out to his Father on the cross (15:34). The criminal charge posted at the cross (“Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews”) was written in three languages—Aramaic, Latin, and Greek—to cover the relevant languages of the time (John 19:20). But there is no single language of Christianity.

The Diversity of the Early Church

It is a common misconception that Christianity first came to Africa via white missionaries in the colonial era. In the New Testament, we meet a highly educated African man who became a follower of Jesus centuries before Christianity penetrated Britain or America. In Acts 8, God directs the apostle Philip to the chariot of an Ethiopian eunuch. The man was “a court official of Candace, queen of the Ethiopians, who was in charge of all her treasure” (Acts 8:27, ESV). Philip hears the Ethiopian reading from the Book of Isaiah and explains that Isaiah was prophesying about Jesus. The Ethiopian immediately embraces Christ and asks to be baptized (Acts 8:26–40).

We don’t know how people responded when the Ethiopian eunuch took the gospel home. But we do know that in the fourth century, two slave brothers precipitated the Christianization of Ethiopia and Eritrea, which led to the founding of the second officially Christian state in the world. We also know that Christianity took root in Egypt in the first century and spread by the second century to Tunisia, the Sudan, and other parts of Africa.

Furthermore, Africa spawned several of the early church fathers, including one of the most influential theologians in Christian history: the fourth-century scholar Augustine of Hippo. Likewise, until they were all but decimated by persecution, Iraq was home to one of the oldest continuous Christian communities in the world. And returning to Sengmei’s homeland, far from only being reached in the colonial era, the church in India claims a lineage going back to the first century. While this is impossible to verify, leading scholar Robert Eric Frykenberg concludes, “It seems certain that there were well-established communities of Christians in South India no later than the third and fourth centuries, and perhaps much earlier.” Thus, Christianity likely took root in India centuries before the Christianization of Britain.

Every Tribe, Tongue, and Nation

Many of us associate Christianity with white, Western imperialism. There are reasons for this—some quite ugly, regrettable reasons. But most of the world’s Christians are neither white nor Western, and Christianity is getting less white and less Western by the day.

Today, Christianity is the largest and most diverse belief system in the world, representing the most even racial and cultural spread, with roughly equal numbers of self-identifying Christians living in Europe, North America, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa. Over 60 percent of Christians live in the Global South, and the center of gravity for Christianity in the coming decades will likely be increasingly non-Western.

According to Pew Reseach Center, by 2060, sub-Saharan Africa could be home to 40 percent of the world’s self-identifying Christians. And while China is currently the global center of atheism, Christianity is spreading there so quickly that China could have the largest Christian population in the world by 2025 and could be a majority-Christian country by 2050, according to Purdue University sociologist Fenggang Yang.

To be clear: The fact that Christianity has been a multicultural, multiracial, multiethnic movement since its inception does not excuse the ways in which Westerners have abused Christian identity to crush other cultures. After the conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine in the fourth century, Western Christianity went from being the faith of a persecuted minority to being linked with the political power of an empire—and power is perhaps humanity’s most dangerous drug.

But, ironically, our habit of equating Christianity with Western culture is itself an act of Western bias. The last book of the Bible paints a picture of the end of time, when “a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language” will worship Jesus (Rev. 7:9). This was the multicultural vision of Christianity in the beginning. For all the wrong turns made by Western Christians in the last 2,000 years, when we look at church growth globally today, it is not crazy to think that this vision could ultimately be realized. So let’s attend to biblical theology, church history, and contemporary sociology of religion and, as my friend Kanato Chopi put it, let’s abandon this absurd idea that Christianity is a Western religion.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed