The Heart of Jesus Ministry

was his

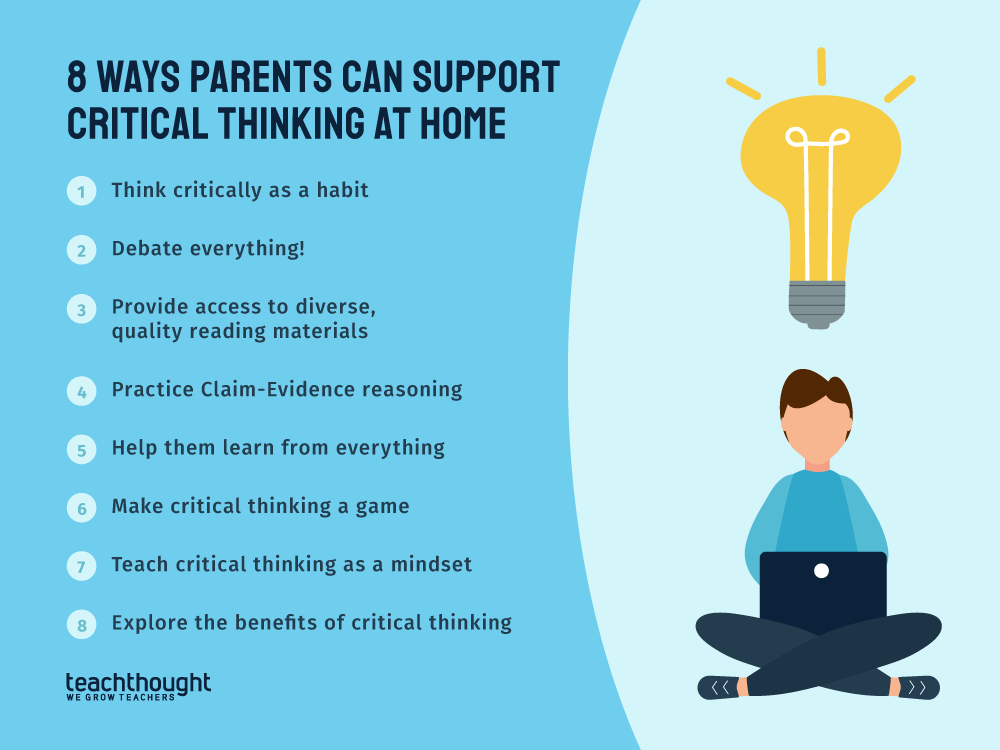

affective teaching method

when using

Parables

Jesus was a wanderer, much like the

Prodigal Son, but on the REVERSE

flip side,

his life experience lead THE WAY to being

nothing short of a Prodigy

in the

game of life

Spades; How to Keep Score

making the contract

(the number of tricks bid), the player scores 10 points for each trick bid,

plus 1 point for each overtrick.

For example, if the player's bid is Seven

and they make seven tricks, the score would be 70.

If the bid was Five

and the player won eight tricks, the score would be 53 points:

50 points for the bid, and 3 points for the three overtricks. In some games, overtricks are called "bags" and a deduction of 100 points is made every time a player accumulates 10 bags.

Thus, the object is always to

fulfill the bid exactly

If the player "breaks contract,"

that is,

if they take fewer than the number of tricks bid,

the score is 0

For example, if a player bids Four

and wins only three tricks, no points are awarded.

One of the players is the scorer and

writes the bids down,

so that during the play and for the

scoring afterward,

this information

will be available to

all the players

When a hand is over, the scores should be recorded next to the bids, and a running score should be kept so that players can readily see each other's total points. If there is a tie, then all players participate in one more round of play.

Jesus has plenty to say

about winning, loosing, and how to

play your hand fair in the game of life...so

Coin Purses are a really Handy

investment, especially at a Good Cost!

The Parables of the Lost Sheep and the

Lost Coin

(Luke 15:3–10) are the first two in a series of three.

The third is the “lost son” or the “prodigal son.” Just as in other cases, Jesus taught these parables in a set of three to emphasize His point. To properly understand the message of these parables, we must recognize exactly what a parable is, and why it is used.

What is a parable?

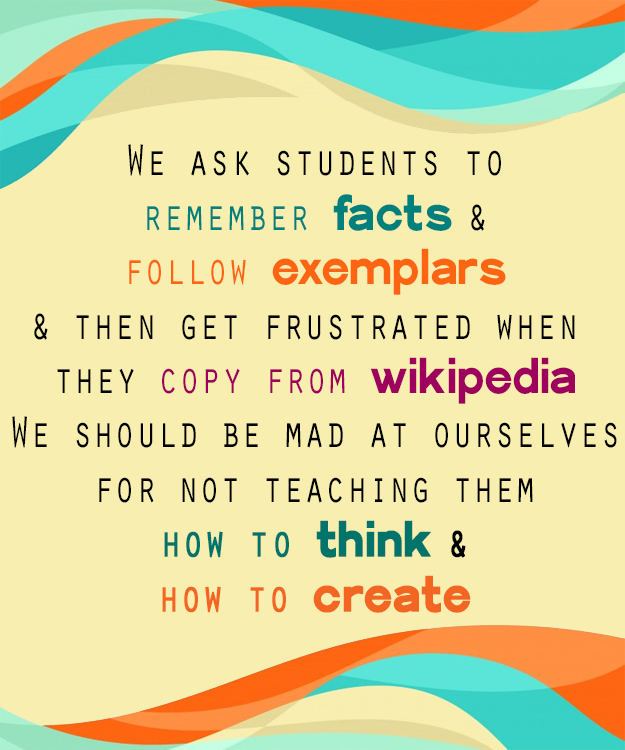

At a basic level, a parable is a short story designed to convey a concept to be understood and/or a principle to be put into practice. This, however, tells us more about the intent of a parable than what it actually is. The word “parable” in Greek literally means, “to set beside,” as in the English word “comparison” or “similitude.” In the Jewish culture, things were explained not in terms of statistics or definitions as they are in English-speaking cultures. In the Jewish culture of biblical times, things were explained in word pictures.

Why did Jesus use parables?

Word pictures do not draw attention to technicalities (like the Jewish law) but to attitudes, concepts, and characteristics. Jesus was speaking a language that all Jews could understand, but with an emphasis on attitudes rather than the outward appearances that the Pharisees focused on (John 7:24). Parables also have an emotional impact that makes them more meaningful and memorable to those who are soft of heart. At the same time, the parables of Jesus often times remained a mystery to those with a hardened heart because parables require the listeners to be self-critical and put themselves in the appropriate place in the story. The result was that the Pharisees would “be ever hearing, but never understanding; be ever seeing, but never perceiving” (Isaiah 6:9; Psalm 78:2; Matthew 13:35).

By using parables, the teaching of Jesus remains timeless despite most changes in culture, time, and technology. For example, these two parables convey commonly understood concepts like grace, gentleness, concern, pride and others, all of which we can be understood by us, even though the story is over two thousand years old. In Jewish culture character traits are often described in relation to objects that are universally recognized like the regularity of the sun or the refreshing nature of rain (Hosea 6:3). This also explains why poetry is the most common mode of language used in the Bible. In the case of parables specifically, the elements mentioned in them are usually representations of something else, just as in an allegory. However, an overemphasis on a particular detail in a parable tends to lead to interpretive errors. Repetitions, patterns, or changes will often help us in identifying when we should focus on a particular detail.

Why Jesus taught these parables

Let us look at the particular details of these parables. The situation in which Jesus is speaking can be seen in Luke 15:1–2. “Now the tax collectors and ‘sinners’ were all gathering around to hear him. But the Pharisees and the teachers of the law muttered, ‘This man welcomes sinners and eats with them’” (NIV). Notice that the Pharisees did not complain that Jesus is teaching sinners.

Since the Pharisees thought

themselves to be righteous

"teachers of the LAW"

and

all "others" to be wicked,

they could not condemn His preaching to “sinners,”

but they thought it was inconsistent with the

dignity of someone

so

knowledgeable in the Scriptures

to “eat with them.”

The presupposition behind the statement

of the Pharisees,

“this man welcomes sinners,”

is what

Jesus addresses

in all three parables

To understand the significance of the opening

statement in chapter 15,

we must consider that the

Jewish culture is a

"shame-honor-driven society"

that

used "shame-honor" in a way that

developed a sort of "caste system"

Who thinks it be wise to cast out the

Living God of the Universe,

and ought

throw the first stone?

Virtually everything that is done in Jewish culture brings either shame or honor. The primary motivation for what and how things are done is based on

seeking honor for oneself

and avoiding shame.

This was the central and

all-consuming preoccupation

of all

Jewish interaction.

In the first parable, Jesus invites His listeners to place themselves into the story with, “Suppose one of you has a hundred sheep.” In doing this Jesus is appealing to their intuitive reasoning and life experiences. As the story completes, the Pharisees in their pride refuse to see themselves as shameful “sinners,” but eagerly take the honoring label of being “righteous.” However, by the implication of their own pride, they place themselves in the position of being the less significant group of ninety-nine: “There will be more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who do not need to repent.”

There may be a bit of sarcasm in the reference to the

Pharisees

“who do not need to repent”

(see Romans 3:23).

In the “lost coin” parable, the ten silver coins refers to a piece of jewelry with ten silver coins on it worn by brides. This was the equivalent of a wedding ring in modern times.

Upon careful examination of the parables, we can see that Jesus was turning His listeners’ understanding of things upside down. The Pharisees saw themselves as being the beloved of God and the “sinners” as refuse. Jesus uses the Pharisees’ prejudices against them, while encouraging the sinners with one clear message. That message is this: God has a tender, personal concern (“and when he finds it, he puts it on his shoulders,” v. 5). God has a joyous love for individuals who are lost (in sin) and are found (repent). Jesus makes it clear that the Pharisees, who thought they were close to God, were actually distant and those sinners and tax collectors were the ones God was seeking after. We see this same message in 18:9-14. There, Jesus is teaching on attitudes of prayer, but the problem he is addressing is the same as in chapter 15. In 18:14 Jesus provides the conclusion for us:

"I tell you that this man, rather than the other,

went home justified before God.

Everyone who exalts himself will be humbled,

and he who humbles himself will be exalted.”

Patterns of progression in the parables

By identifying things in common in the parables, we can gain context to help us understand the significance of otherwise subtle elements in the story. As the old saying goes, “Proper context covers a multitude of interpretive errors.” 1) The progression of value: in the first parable a sheep is lost, then a silver coin in the next, followed by a son in the third. As mentioned before, part of the power of these parables to reach the audience comes from the shame/honor aspect of their culture. To lose a sheep as a shepherd would be a very shameful thing, a coin from a piece of bridal jewelry lost in her own house would be more shameful, followed by the lost son, which was the worst of all in Jewish culture. 2) The personal progression from seeking after only 1 of 100 sheep, then 1 of 10 coins, then 1 of 2 sons. This shows the scope of God’s personal concern for individuals and would have been of great comfort to the “sinners” Jesus was teaching. 3) A change in tense in each parable regarding the rejoicing at that which was found, from future tense, to present, and then to past tense: “will be more joy” to “there is joy” and finally “had to be.” This may have communicated the certainty of God’s acceptance of those who repent. 4) The progression of earthly references to what the thing was lost in (a subtle reference to sin). The sheep was lost in open fields, the coin was lost in the dirt that was swept up, and son was in the mud of a pigsty before coming to his senses. 5) The relational power of each parable: Poor men and young boys would have related best to the shepherd and the lost sheep. Women would have related best to the lost bridal coin. The last parable dealt with everyone present by dealing with the relationship of a father and son.

Patterns of Consistency in the parables

1) The main character possesses something valuable and does not want to lose it.

2) The main character rejoices in the finding of the lost thing, but does not rejoice alone.

3) The main character (God) expresses care in either the looking or the handling of that which was lost.

4) Each thing that was lost has a personal value, not just a monetary value: shepherds care for their sheep, women cherish their bridal jewelry, and a father loves his son.

Incidentally, this first illustration of the shepherd carrying the sheep on his shoulders was the original figure used to identify Christians before people began identifying Christianity with crosses. In these parables Jesus paints with words a beautiful picture of God’s grace in His desire to see the lost return to Him. Men seek honor and avoid shame; God seeks to glorify Himself through us His sheep, His sons and daughters. Despite having ninety-nine other sheep, despite the sinful rebellion of His lost sheep, God joyfully receives it back, just as He does when we repent and return to Him.

The Parable of the Good Samaritan is precipitated by and in answer to a question posed to Jesus by a lawyer. In this case the lawyer would have been an expert in the Mosaic Law and not a court lawyer of today. The lawyer’s question was, “Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?" (Luke 10:25). This question provided Jesus with an opportunity to define what His disciples’ relationship should be to their neighbors. The text says that the scribe (lawyer) had put the question to Jesus as a test, but the text does not indicate that there was hostility in the question. He could have simply been seeking information. The wording of the question does, however, give us some insight into where the scribe’s heart was spiritually. He was making the assumption that man must do something to obtain eternal life. Although this could have been an opportunity for Jesus to discuss salvation issues, He chose a different course and focuses on our relationships and what it means to love.

Jesus answers the question using what is called the Socratic method; i.e., answering a question with a question: “He said to him, ‘What is written in the law? What is your reading of it?’" (Luke 10:26). By referring to the Law, Jesus is directing the man to an authority they both would accept as truth, the Old Testament. In essence, He is asking the scribe, what does Scripture say about this and how does he interpret it? Jesus thus avoids an argument and puts Himself in the position of evaluating the scribe’s answer instead of the scribe evaluating His answer. This directs the discussion towards Jesus’ intended lesson. The scribe answers Jesus’ question by quoting Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18. This is virtually the same answer that Jesus had given to the same question in Matthew 22 and Mark 12.

In verse 28, Jesus affirms that the lawyer’s answer is correct. Jesus’ reply tells the scribe that he has given an orthodox (scripturally proper) answer, but then goes on in verse 28 to tell him that this kind of love requires more than an emotional feeling; it would also include orthodox practice; he would need to “practice what he preached.” The scribe was an educated man and realized that he could not possibly keep that law, nor would he have necessarily wanted to. There would always be people in his life that he could not love. Thus, he tries to limit the law’s command by limiting its parameters and asked the question “who is my neighbor?” The word “neighbor” in the Greek means “someone who is near,” and in the Hebrew it means “someone that you have an association with.” This interprets the word in a limited sense, referring to a fellow Jew and would have excluded Samaritans, Romans, and other foreigners. Jesus then gives the parable of the Good Samaritan to correct the false understanding that the scribe had of who his neighbor is, and what his duty is to his neighbor.

The Parable of the Good Samaritan tells the story of a man traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho, and while on the way he is robbed of everything he had, including his clothing, and is beaten to within an inch of his life. That road was treacherously winding and was a favorite hideout of robbers and thieves. The next character Jesus introduces into His story is a priest. He spends no time describing the priest and only tells of how he showed no love or compassion for the man by failing to help him and passing on the other side of the road so as not to get involved. If there was anyone who would have known God’s law of love, it would have been the priest. By nature of his position, he was to be a person of compassion, desiring to help others. Unfortunately, “love” was not a word for him that required action on the behalf of someone else. The next person to pass by in the Parable of the Good Samaritan is a Levite, and he does exactly what the priest did: he passes by without showing any compassion. Again, he would have known the law, but he also failed to show the injured man compassion.

The next person to come by is the Samaritan, the one least likely to have shown compassion for the man. Samaritans were considered a low class of people by the Jews since they had intermarried with non-Jews and did not keep all the law. Therefore, Jews would have nothing to do with them. We do not know if the injured man was a Jew or Gentile, but it made no difference to the Samaritan; he did not consider the man’s race or religion. The “Good Samaritan” saw only a person in dire need of assistance, and assist him he did, above and beyond the minimum required. He dresses the man’s wounds with wine (to disinfect) and oil (to sooth the pain). He puts the man on his animal and takes him to an inn for a time of healing and pays the innkeeper with his own money. He then goes beyond common decency and tells the innkeeper to take good care of the man, and he would pay for any extra expenses on his return trip. The Samaritan saw his neighbor as anyone who was in need.

Because the good man was a Samaritan, Jesus is drawing a strong contrast between those who knew the law and those who actually followed the law in their lifestyle and conduct. Jesus now asks the lawyer if he can apply the lesson to his own life with the question “So which of these three do you think was neighbor to him who fell among the thieves?" (Luke 10:36). Once again, the lawyer’s answer is telling of his personal hardness of heart. He cannot bring himself to say the word “Samaritan”; he refers to the “good man” as “he who showed mercy.” His hate for the Samaritans (his neighbors) was so strong that he couldn’t even refer to them in a proper way. Jesus then tells the lawyer to “go and do likewise,” meaning that he should start living what the law tells him to do.

By ending the encounter in this manner, Jesus is telling us to follow the Samaritan’s example in our own conduct; i.e., we are to show compassion and love for those we encounter in our everyday activities. We are to love others (vs. 27) regardless of their race or religion; the criterion is need. If they need and we have the supply, then we are to give generously and freely, without expectation of return. This is an impossible obligation for the lawyer, and for us. We cannot always keep the law because of our human condition; our heart and desires are mostly of self and selfishness. When left to our own, we do the wrong thing, failing to meet the law. We can hope that the lawyer saw this and came to the realization that there was nothing he could do to justify himself, that he needed a personal savior to atone for his lack of ability to save himself from his sins. Thus, the lessons of the Parable of the Good Samaritan are three-fold: (1) we are to set aside our prejudice and show love and compassion for others. (2) Our neighbor is anyone we encounter; we are all creatures of the creator and we are to love all of mankind as Jesus has taught. (3) Keeping the law in its entirety with the intent to save ourselves is an impossible task; we need a savior, and this is Jesus.

There is another possible way to interpret the Parable of the Good Samaritan, and that is as a metaphor. In this interpretation the injured man is all men in their fallen condition of sin. The robbers are Satan attacking man with the intent of destroying their relationship with God. The lawyer is mankind without the true understanding of God and His Word. The priest is religion in an apostate condition. The Levite is legalism that instills prejudice into the hearts of believers. The Samaritan is Jesus who provides the way to spiritual health. Although this interpretation teaches good lessons, and the parallels between Jesus and the Samaritan are striking, this understanding draws attention to Jesus that does not appear to be intended in the text. Therefore, we must conclude that the teaching of the Parable of the Good Samaritan is simply a lesson on what it means to love one’s neighbor.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed