There is no doubt that Jesus has, by far, the highest name recognition throughout the world. Fully one-third of our world’s population—about 2.5 billion people—call themselves Christians. Islam, which comprises about 1.5 billion people, actually recognizes Jesus as the second greatest prophet after Mohammed. Of the remaining 3.2 billion people (roughly half the world’s population), most have either heard of the name of Jesus or know about Him.

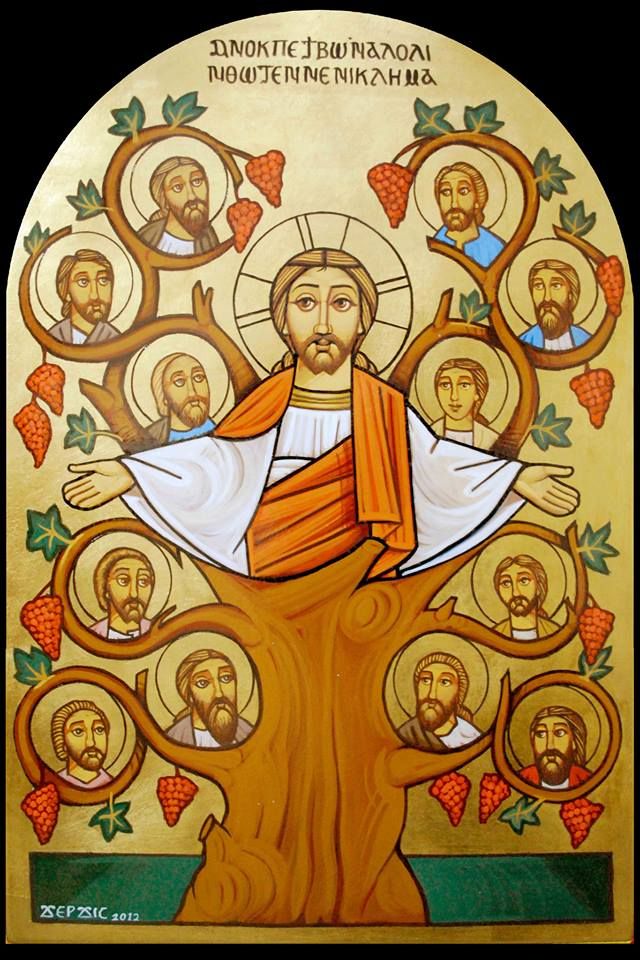

If one were to put together a summary of the life of Jesus from His birth to His death, it would be somewhat sparse. He was born of Jewish parents in Bethlehem, a small town south of Jerusalem, while the territory was under Roman occupation. His parents moved north to Nazareth, where He grew up; hence He was commonly known as “Jesus of Nazareth.” His father was a carpenter, so Jesus likely learned that trade in His early years. Around thirty years of age, He began a public ministry. He chose a dozen men of dubious reputation as His disciples and worked out of Capernaum, a large fishing village and trading center on the coast of the Sea of Galilee. From there He traveled and preached throughout the region of Galilee, often moving among neighboring Gentiles and Samaritans with intermittent journeys to Jerusalem.

Jesus’ unusual teachings and methodology startled and troubled many. His revolutionary message, coupled with astonishing miracles and healings, garnered a huge following. His popularity among the populace grew rapidly, and, as a result, it was noticed by the well-entrenched leaders of the Jewish faith. Soon, these Jewish leaders became jealous and resentful of His success. Many of these leaders found His teachings offensive and felt that their established religious traditions and ceremonies were being jeopardized. They soon plotted with the Roman rulers to have Him killed. It was during this time that one of Jesus’ disciples betrayed Him to the Jewish leaders for a paltry sum of money. Shortly thereafter, they had Him arrested, engineered a hastily arranged series of mock trials, and summarily executed Him by crucifixion.

But unlike any other in history, Jesus’ death was not the end of His story; it was, in fact, the beginning. Christianity exists only because of what happened after Jesus died. Three days after His death, His disciples and many others began to claim that He had returned to life from the dead. His grave was found empty, the body gone, and numerous appearances were witnessed by many different groups of people, at different locations, and among dissimilar circumstances.

As a result of all this, people began to proclaim that Jesus was the Christ, or the Messiah. They claimed His resurrection validated the message of forgiveness of sin through His sacrifice. At first, they declared this good news, known as the gospel, in Jerusalem, the same city where He was put to death. This new following soon became known as the Way (see Acts 9:2; Acts 19:9; Acts 19:23; Acts 24:22) and expanded rapidly. In a short period of time, this gospel message of faith spread even beyond the region, expanding as far as Rome as well as to the very outermost of its vast empire.

It was Dr. James Allan Francis who penned the following words that aptly describe the influence of Jesus through the history of mankind:

"Here is a man who was born in an obscure village, the child of a peasant woman. He grew up in another village. He worked in a carpenter shop until He was thirty. Then for three years He was an itinerant preacher.

"He never owned a home. He never wrote a book. He never held an office. He never had a family. He never went to college. He never put His foot inside a big city. He never traveled two hundred miles from the place He was born. He never did one of the things that usually accompany greatness. He had no credentials but Himself. . . .

"While still a young man, the tide of popular opinion turned against Him. His friends ran away. One of them denied Him. He was turned over to His enemies. He went through the mockery of a trial. He was nailed upon a cross between two thieves. While He was dying His executioners gambled for the only piece of property He had on earth—His coat. When He was dead, He was laid in a borrowed grave through the pity of a friend.

"Nineteen long centuries have come and gone, and today He is a centerpiece of the human race and leader of the column of progress.

"I am far within the mark when I say that all the armies that ever marched, all the navies that were ever built; all the parliaments that ever sat and all the kings that ever reigned, put together, have not affected the life of man upon this earth as powerfully as has that one solitary life."

The late Wilbur Smith, respected Bible scholar of the last generation, once wrote, “The latest edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica gives twenty thousand words to this person, Jesus, and does not even hint that He did not exist—more words, by the way, than are given to Aristotle, Alexander, Cicero, Julius Caesar, or Napoleon Bonaparte.”

George Buttrick, recognized as one of the ten greatest preachers of the twentieth century, wrote: “Jesus gave history a new beginning. In every land he is at home. . . . His birthday is kept across the world. His death-day set a gallows against every skyline.”

Even Napoleon himself admitted, "I know men and I tell you that Jesus Christ was no mere man: between him and whoever else in the world there is no possible term of comparison."

Christianity in the 1st century covers the formative history of Christianity from the start of the ministry of Jesus (c. 27–29 AD) to the death of the last of the Twelve Apostles (c. 100) and is thus also known as the Apostolic Age. Early Christianity developed out of the eschatologicalministry of Jesus. Subsequent to Jesus' death, his earliest followers formed an apocalyptic messianic Jewish sect during the late Second Temple period of the 1st century. Initially believing that Jesus' resurrection was the start of the end time, their beliefs soon changed in the expected Second Coming of Jesus and the start of God's Kingdom at a later point in time.

Paul the Apostle, a Pharisee Jew who had persecuted the early Jewish Christians, converted c. 33–36[2][3][4] and started to proselytize among the Gentiles. According to Paul, Gentile converts could be allowed exemption from Jewish commandments, arguing that all are justified by their faith in Jesus.[5][6] This was part of a gradual split of early Christianity and Judaism, as Christianity became a distinct religion including predominantly Gentile adherence.

Jerusalem had an early Christian community, which was led by James the Just, Peter, and John.[7] According to Acts 11:26, Antioch was where the followers were first called Christians. Peter was later martyred in Rome, the capital of the Roman Empire. The apostles went on to spread the message of the Gospel around the classical world and founded apostolic sees around the early centers of Christianity. The last apostle to die was John in c. 100.

Early Jewish Christians referred to themselves as "The Way" (ἡ ὁδός), probably coming from Isaiah 40:3, "prepare the way of the Lord."[web 1][web 2][9][10][note 1] Other Jews also called them "the Nazarenes,"[9] while another Jewish-Christian sect called themselves "Ebionites" (lit. "the poor"). According to Acts 11:26, the term "Christian" (Greek: Χριστιανός) was first used in reference to Jesus's disciples in the city of Antioch, meaning "followers of Christ," by the non-Jewish inhabitants of Antioch.[12] The earliest recorded use of the term "Christianity" (Greek: Χριστιανισμός) was by Ignatius of Antioch, in around 100 AD.

The earliest followers of Jesus were a sect of apocalyptic Jewish Christians within the realm of Second Temple Judaism.[14][15][16][17][18] The early Christian groups were strictly Jewish, such as the Ebionites,[14] and the early Christian community in Jerusalem, led by James the Just, brother of Jesus.[17] Christianity "emerged as a sect of Judaism in Roman Palestine"[19] in the syncretistic Hellenistic world of the first century AD, which was dominated by Roman law and Greek culture.[20] Hellenistic culture had a profound impact on the customs and practices of Jews everywhere. The inroads into Judaism gave rise to Hellenistic Judaism in the Jewish diaspora which sought to establish a Hebraic-Jewish religious tradition within the culture and language of Hellenism. Hellenistic Judaism spread to Ptolemaic Egypt from the 3rd century BC, and became a notable religio licita after the Roman conquest of Greece, Anatolia, Syria, Judea, and Egypt.[citation needed]

During the early first century AD there were many competing Jewish sects in the Holy Land, and those that became Rabbinic Judaism and Proto-orthodox Christianity were but two of these. Philosophical schools included Pharisees, Sadducees, and Zealots, but also other less influential sects, including the Essenes.[web 7][web 8][citation needed] The first century BC and first century AD saw a growing number of charismatic religious leaders contributing to what would become the Mishnah of Rabbinic Judaism; and the ministry of Jesus, which would lead to the emergence of the first Jewish Christian community.[web 7][web 8][citation needed]

A central concern in 1st century Judaism was the covenant with God, and the status of the Jews as the chosen people of God.[21] Many Jews believed that this covenant would be renewed with the coming of the Messiah. Jews believed the Law was given by God to guide them in their worship of the Lord and in their interactions with each other, "the greatest gift God had given his people."

The Jewish messiah concept has its root in the apocalyptic literature of the 2nd century BC to 1st century BC, promising a future leader or king from the Davidic line who is expected to be anointed with holy anointing oil and rule the Jewish people during the Messianic Age and world to come.[web 9][web 10][web 11] The Messiah is often referred to as "King Messiah" (Hebrew: מלך משיח, romanized: melekh mashiach) or malka meshiḥa in Aramaic.

Jesus' life was ended by his execution by crucifixion. His early followers believed that three days after his death, Jesus rose bodily from the dead.[67][68][69][70][71] Paul's letters and the Gospels contain reports of a number of post-resurrection appearances. Progressively, Jewish scriptures were reexamined in light of Jesus's teachings to explain the crucifixion and visionary post-mortem experiences of Jesus,[1][77][78] and the resurrection of Jesus "signalled for earliest believers that the days of eschatological fulfilment were at hand."

Traditionally, the period from the death of Jesus until the death of the last of the Twelve Apostles is called the Apostolic Age, after the missionary activities of the apostles.[85] According to the Acts of the Apostles the Jerusalem church began at Pentecost with some 120 believers,[86] in an "upper room," believed by some to be the Cenacle, where the apostles received the Holy Spirit and emerged from hiding following the death and resurrection of Jesus to preach and spread his message.

The New Testament writings depict what orthodox Christian churches call the Great Commission, an event where they describe the resurrected Jesus Christ instructing his disciples to spread his eschatological message of the coming of the Kingdom of God to all the nations of the world. The most famous version of the Great Commission is in Matthew 28 (Matthew 28:16–20), where on a mountain in Galilee Jesus calls on his followers to make disciples of and baptize all nations in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Paul's conversion on the Road to Damascus is first recorded in Acts 9 (Acts 9:13–16). Peter baptized the Roman centurion Cornelius, traditionally considered the first Gentile convert to Christianity, in Acts 10. Based on this, the Antioch church was founded. It is also believed that it was there that the term Christian was coined.

After the death of Jesus, Christianity first emerged as a sect of Judaism as practiced in the Roman province of Judea.[19] The first Christians were all Jews, who constituted a Second Temple Jewish sect with an apocalyptic eschatology. Among other schools of thought, some Jews regarded Jesus as Lord and resurrected messiah, and the eternally existing Son of God,[7][90][note 8] expecting the second coming of Jesus and the start of God's Kingdom. They pressed fellow Jews to prepare for these events and to follow "the way" of the Lord. They believed Yahweh to be the only true God,[92] the god of Israel, and considered Jesus to be the messiah (Christ), as prophesied in the Jewish scriptures, which they held to be authoritative and sacred. They held faithfully to the Torah,[note 9]including acceptance of Gentile converts based on a version of the Noachide laws.

The New Testament's Acts of the Apostles (the historical accuracy of which is questioned) and Epistle to the Galatians record that an early Jewish Christian community[note 11] centered on Jerusalem, and that its leaders reportedly included Peter, James, the brother of Jesus, and John the Apostle.[93] The Jerusalem community "held a central place among all the churches," as witnessed by Paul's writings.[94] Reportedly legitimised by Jesus' appearance, Peter was the first leader of the Jerusalem ekklēsia.[95][96] Peter was soon eclipsed in this leadership by James the Just, "the Brother of the Lord,"[97][98] which may explain why the early texts contain scant information about Peter.[98] According to Lüdemann, in the discussions about the strictness of adherence to the Jewish Law, the more conservative faction of James the Just gained the upper hand over the more liberal position of Peter, who soon lost influence.[98] According to Dunn, this was not an "usurpation of power," but a consequence of Peter's involvement in missionary activities.[99] The relatives of Jesus were generally accorded a special position within this community,[100] which also contributed to the ascendancy of James the Just in Jerusalem.

According to a tradition recorded by Eusebius and Epiphanius of Salamis, the Jerusalem church fled to Pella at the outbreak of the First Jewish–Roman War (AD 66–73).

The Jerusalem community consisted of "Hebrews," Jews speaking both Aramaic and Greek, and "Hellenists," Jews speaking only Greek, possibly diaspora Jews who had resettled in Jerusalem.[102] According to Dunn, Paul's initial persecution of Christians probably was directed against these Greek-speaking "Hellenists" due to their anti-Temple attitude.[103] Within the early Jewish Christian community, this also set them apart from the "Hebrews" and their Tabernacle observance.

The Book of Acts reports that the early followers continued daily Temple attendance and traditional Jewish home prayer, Jewish liturgical, a set of scriptural readings adapted from synagogue practice, and use of sacred music in hymns and prayer. Other passages in the New Testament gospels reflect a similar observance of traditional Jewish piety such as baptism,[web 22] fasting, reverence for the Torah, and observance of Jewish holy days.

During the first three centuries of Christianity, the Liturgical ritual was rooted in the Jewish Passover, Siddur, Seder, and synagogue services, including the singing of hymns (especially the Psalms) and reading from the scriptures.[web 23] Most early Christians did not own a copy of the works (some of which were still being written) that later became the Christian Bibleor other church works accepted by some but not canonized, such as the writings of the Apostolic Fathers, or other works today called New Testament apocrypha. Similar to Judaism, much of the original church liturgical services functioned as a means of learning these scriptures, which initially centered around the Septuagint and the Targums.

At first, Christians continued to worship alongside Jewish believers, but within twenty years of Jesus' death, Sunday (the Lord's Day) was being regarded as the primary day of worship.

Christian missionary activity spread "the Way" and slowly created early centers of Christianity with Gentile adherents in the predominantly Greek-speaking eastern half of the Roman Empire, and then throughout the Hellenistic world and even beyond the Roman Empire. Early Christian beliefs were proclaimed in kerygma (preaching), some of which are preserved in New Testament scripture. The early Gospel message spread orally, probably originally in Aramaic,[151] but almost immediately also in Greek.[152] A process of cognitive dissonance reduction may have contributed to intensive missionary activity, convincing others of the developing beliefs, reducing the cognitive dissonance created by the delay of the coming of the endtime. Due to this missionary zeal, the early group of followers grew larger despite the failing expectations.

The scope of the Jewish-Christian mission expanded over time. While Jesus limited his message to a Jewish audience in Galilee and Judea, after his death his followers extended their outreach to all of Israel, and eventually the whole Jewish diaspora, believing that the Second Coming would only happen when all Jews had received the Gospel.[1] Apostles and preachers traveled to Jewish communities around the Mediterranean Sea, and initially attracted Jewish converts.[149] Within 10 years of the death of Jesus, apostles had attracted enthusiasts for "the Way" from Jerusalem to Antioch, Ephesus, Corinth, Thessalonica, Cyprus, Crete, Alexandria and Rome.[153][87][148][149] Over 40 churches were established by 100,[148][149] most in Asia Minor, such as the seven churches of Asia, and some in Greece in the Roman era and Roman Italy.

According to Fredriksen, when early Christians broadened their missionary efforts, they also came into contact with Gentiles attracted to the Jewish religion. Eventually, the Gentiles came to be included in the missionary effort of Hellenised Jews, bringing "all nations" into the house of God.[1] The "Hellenists," Greek-speaking diaspora Jews belonging to the early Jerusalem Jesus-movement, played an important role in reaching a Gentile, Greek audience, notably at Antioch, which had a large Jewish community and significant numbers of Gentile "God-fearers."[147] From Antioch, the mission to the Gentiles started, including Paul's, which would fundamentally change the character of the early Christian movement, eventually turning it into a new, Gentile religion.[154] According to Dunn, within 10 years after Jesus' death, "the new messianic movement focused on Jesus began to modulate into something different ... it was at Antioch that we can begin to speak of the new movement as 'Christianity'."

Paul's influence on Christian thinking is said to be more significant than that of any other New Testament author.[158] According to the New Testament, Saul of Tarsus first persecuted the early Jewish Christians, but then converted. He adopted the name Paul and started proselytizingamong the Gentiles, calling himself "Apostle to the Gentiles."

Paul was in contact with the early Christian community in Jerusalem, led by James the Just.[161] According to Mack, he may have been converted to another early strand of Christianity, with a High Christology.[162] Fragments of their beliefs in an exalted and deified Jesus, what Mack called the "Christ cult," can be found in the writings of Paul.[161][note 18] Yet, Hurtado notes that Paul valued the linkage with "Jewish Christian circles in Roman Judea," which makes it likely that his Christology was in line with, and indebted to, their views.[164] Hurtado further notes that "[i]t is widely accepted that the tradition that Paul recites in 1 Corinthians 15:1-7 must go back to the Jerusalem Church."

Paul was responsible for bringing Christianity to Ephesus, Corinth, Philippi, and Thessalonica.[166][better source needed] According to Larry Hurtado, "Paul saw Jesus' resurrection as ushering in the eschatological time foretold by biblical prophets in which the pagan 'Gentile' nations would turn from their idols and embrace the one true God of Israel (e.g., Zechariah 8:20–23), and Paul saw himself as specially called by God to declare God's eschatological acceptance of the Gentiles and summon them to turn to God."[web 1] According to Krister Stendahl, the main concern of Paul's writings on Jesus' role and salvation by faith is not the individual conscience of human sinners and their doubts about being chosen by God or not, but the main concern is the problem of the inclusion of Gentile (Greek) Torah-observers into God's covenant.[167][168][169][web 25] The inclusion of Gentiles into early Christianity posed a problem for the Jewish identity of some of the early Christians:[170][171][172] the new Gentile converts were not required to be circumcised nor to observe the Mosaic Law.[173] Circumcision in particular was regarded as a token of the membership of the Abrahamic covenant, and the most traditionalist faction of Jewish Christians (i.e., converted Pharisees) insisted that Gentile converts had to be circumcised as well.[Acts 15:1][170][171][174][166] By contrast, the rite of circumcision was considered execrable and repulsive during the period of Hellenization of the Eastern Mediterranean,[175] [176][177][web 26] and was especially adversed in Classical civilization both from ancient Greeks and Romans, which instead valued the foreskin positively.

Paul objected strongly to the insistence on keeping all of the Jewish commandments,[166] considering it a great threat to his doctrine of salvation through faith in Christ.[171][179]According to Paula Fredriksen, Paul's opposition to male circumcison for Gentiles is in line with the Old Testament predictions that "in the last days the gentile nations would come to the God of Israel, as gentiles (e.g., Zechariah 8:20–23), not as proselytes to Israel."[web 16] For Paul, Gentile male circumcision was therefore an affront to God's intentions.[web 16]According to Larry Hurtado, "Paul saw himself as what Munck called a salvation-historical figure in his own right", who was "personally and singularly deputized by God to bring about the predicted ingathering (the "fullness") of the nations (Romans 11:25)."

For Paul, Jesus' death and resurrection solved the problem of the exclusion of Gentiles from God's covenant,[180][181] since the faithful are redeemed by participation in Jesus' death and rising. In the Jerusalem ekklēsia, from which Paul received the creed of 1 Corinthians 15:1–7, the phrase "died for our sins" probably was an apologetic rationale for the death of Jesus as being part of God's plan and purpose, as evidenced in the Scriptures. For Paul, it gained a deeper significance, providing "a basis for the salvation of sinful Gentiles apart from the Torah."[182] According to E. P. Sanders, Paul argued that "those who are baptized into Christ are baptized into his death, and thus they escape the power of sin [...] he died so that the believers may die with him and consequently live with him."[web 27] By this participation in Christ's death and rising, "one receives forgiveness for past offences, is liberated from the powers of sin, and receives the Spirit."[183] Paul insists that salvation is received by the grace of God; according to Sanders, this insistence is in line with Second Temple Judaism of c. 200 BC until 200 AD, which saw God's covenant with Israel as an act of grace of God. Observance of the Law is needed to maintain the covenant, but the covenant is not earned by observing the Law, but by the grace of God.

These divergent interpretations have a prominent place in both Paul's writings and in Acts. According to Galatians 2:1–10 and Acts chapter 15, fourteen years after his conversion Paul visited the "Pillars of Jerusalem", the leaders of the Jerusalem ekklēsia. His purpose was to compare his Gospel[clarification needed] with theirs, an event known as the Council of Jerusalem. According to Paul, in his letter to the Galatians,[note 19] they agreed that his mission was to be among the Gentiles. According to Acts,[184] Paul made an argument that circumcision was not a necessary practice, vocally supported by Peter.

While the Church of Jerusalem was described as resulting in an agreement to allow Gentile converts exemption from most Jewish commandments, in reality a stark opposition from "Hebrew" Jewish Christians remained,[188] as exemplified by the Ebionites. The relaxing of requirements in Pauline Christianity opened the way for a much larger Christian Church, extending far beyond the Jewish community. The inclusion of Gentiles is reflected in Luke-Acts, which is an attempt to answer a theological problem, namely how the Messiah of the Jews came to have an overwhelmingly non-Jewish church; the answer it provides, and its central theme, is that the message of Christ was sent to the Gentiles because the Jews rejected it.

The New Testament (often compared to the New Covenant) is the second major division of the Christian Bible. The books of the canon of the New Testament include the Canonical Gospels, Acts, letters of the Apostles, and Revelation. The original texts were written by various authors, most likely sometime between c. AD 45 and 120 AD,[197] in Koine Greek, the lingua franca of the eastern part of the Roman Empire, though there is also a minority argument for Aramaic primacy. They were not defined as "canon" until the 4th century. Some were disputed, known as the Antilegomena.

Writings attributed to the Apostles circulated among the earliest Christian communities. The Pauline epistles were circulating, perhaps in collected forms, by the end of the 1st century AD.

There was a slowly growing chasm between Gentile Christians, and Jews and Jewish Christians, rather than a sudden split. Even though it is commonly thought that Paul established a Gentile church, it took a century for a complete break to manifest. Growing tensions led to a starker separation that was virtually complete by the time Jewish Christians refused to join in the Bar Kokhba Jewish revolt of 132. Certain events are perceived as pivotal in the growing rift between Christianity and Judaism.

The destruction of Jerusalem and the consequent dispersion of Jews and Jewish Christians from the city (after the Bar Kokhba revolt) ended any pre-eminence of the Jewish-Christian leadership in Jerusalem. Early Christianity grew further apart from Judaism to establish itself as a predominantly Gentile religion, and Antioch became the first Gentile Christian community with stature.

The hypothetical Council of Jamnia c. 85 is often stated to have condemned all who claimed the Messiah had already come, and Christianity in particular, excluding them from attending synagogue. However, the formulated prayer in question (birkat ha-minim) is considered by other scholars to be unremarkable in the history of Jewish and Christian relations. There is a paucity of evidence for Jewish persecution of "heretics" in general, or Christians in particular, in the period between 70 and 135. It is probable that the condemnation of Jamnia included many groups, of which the Christians were but one, and did not necessarily mean excommunication. That some of the later church fathers only recommended against synagogue attendance makes it improbable that an anti-Christian prayer was a common part of the synagogue liturgy. Jewish Christians continued to worship in synagogues for centuries.

During the late 1st century, Judaism was a legal religion with the protection of Roman law, worked out in compromise with the Roman state over two centuries (see Anti-Judaism in the Roman Empire for details). In contrast, Christianity was not legalized until the 313 Edict of Milan. Observant Jews had special rights, including the privilege of abstaining from civic pagan rites. Christians were initially identified with the Jewish religion by the Romans, but as they became more distinct, Christianity became a problem for Roman rulers. Around the year 98, the emperor Nerva decreed that Christians did not have to pay the annual tax upon the Jews, effectively recognizing them as distinct from Rabbinic Judaism. This opened the way to Christians being persecuted for disobedience to the emperor, as they refused to worship the state pantheon.

From c. 98 onwards a distinction between Christians and Jews in Roman literature becomes apparent. For example, Pliny the Younger postulates that Christians are not Jews since they do not pay the tax, in his letters to Trajan.

Jewish Christians constituted a separate community from the Pauline Christians but maintained a similar faith. In Christian circles, Nazarene later came to be used as a label for those faithful to Jewish Law, in particular for a certain sect. These Jewish Christians, originally the central group in Christianity, generally holding the same beliefs except in their adherence to Jewish law, were not deemed heretical until the dominance of orthodoxy in the 4th century.[211] The Ebionites may have been a splinter group of Nazarenes, with disagreements over Christology and leadership. They were considered by Gentile Christians to have unorthodox beliefs, particularly in relation to their views of Christ and Gentile converts.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed