But these two did have a sharp encounter.

We see it unfold in Galatians 2:11-19, where Paul rebukes his fellow apostle for caving in to the prejudice of a group who said that people from all ethnic backgrounds had to satisfy the Jewish ritual law -before- they could become proper Christians.

This meant, for instance,

that men had to be circumcised and that no one could eat pork.

Paul was livid at this perversion of the gospel.

They were piling on superfluities,

making salvation a matter of performance instead of

a GIFT of mercy and grace on the basis of faith alone.

If there’s any doubt over how upset Paul was at this heresy, one should read verse 5:12, where he says, “I wish those who unsettle you would emasculate themselves!” In other words, as long as they have the knife out, why stop with circumcision?

They could be even more “holy” if they kept on cutting.

In the fire of Paul’s righteous indignation, Peter got scorched.

He was doing just fine with the brothers in Antioch – until, that is, some Jewish church members came up from Jerusalem.

Before they arrived, he was eating happily with uncircumcised non-Jews in the local fellowship.

But when these “legalists,” these Old Testament Law police,

showed up, he caved in and pulled away from the Gentiles.

Paul spotted his craven behavior and

let him have it in front of these judgmental visitors.

His rebuke and doctrinal lecture make for great gospel reading.

You might think that after such an embarrassing showdown, the two apostles would have had a parting of the ways. Certainly, hurt feelings have wrecked many a relationship. Yet Christianity is not all about feelings, but also and necessarily about truth. And Peter knew that Paul had truth on his side – so much so that in one of his own letters, he commended Paul’s writing as “scripture” (2 Peter 3:15-16). Though he’d been stung by the criticism, he’d been able to “rejoice with truth” in love (1 Corinthians 13:6)

instead of nursing a life-long grudge, which would have hindered his own spiritual development, as well as the witness of the church.

Anyone who’s been around the church for a while recognizes

this sort of clash between admirable believers.

I remember my own shock in seminary when I discovered that missionaries disagreed almost vehemently over strategy, some favoring long-term work from fixed residential, medical, and educational compounds, others insisting that personnel travel light, ever ready to shift from one region to another as circumstances suggested. I thought they all just sang “Kumbaya” and worked by glad consensus at every point.

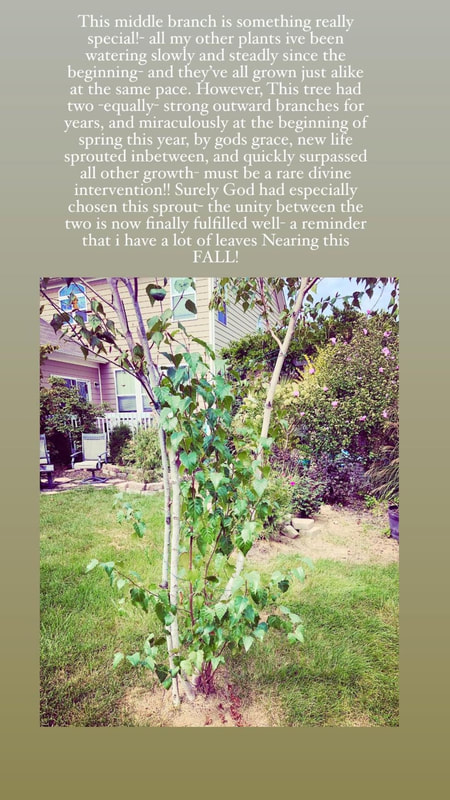

Discord is inevitable when finite, fallen creatures

join together in larger tasks. All Christians are spiritual works-in-progress; they’re being sanctified right along,

but none is perfect, and most are far from it.

Along with their gains in beneficence, courage, and winsomeness,

they have episodes of selfishness, cowardice, and petulance.

And despite their advance in wisdom and knowledge, they’re often just confused. (As a young pastor, I photocopied a quote and put it in my study desk – something along the lines of “Don’t attribute to malice what can be explained in terms of ignorance.”)

In fact, a measure of confusion and sub-Christian moodiness can be at play in all the parties concerned. It’s not always black and white, and often each disputant could use a little rebuke and clarification.

Proverbs 27:17 says as much:

"Iron sharpens iron, and one man sharpens another.”

One thing you have to love about Galatians 2 is its “verisimilitude,” its truthlikeness. You can tell these are real Christians struggling with real limitations, just as we are. The Bible doesn’t gloss over the imperfections of its characters to enhance its spiritual tone. It tells it like it is.

Though the opinions and behavior of the leading figures may be flawed, the reporting of such is accurate, important, and informative.

Paul and Peter were not personally flawless.

They had their self-confessed moments of weakness.

But the Scripture they gave us is inerrant,

by God’s superintendence.

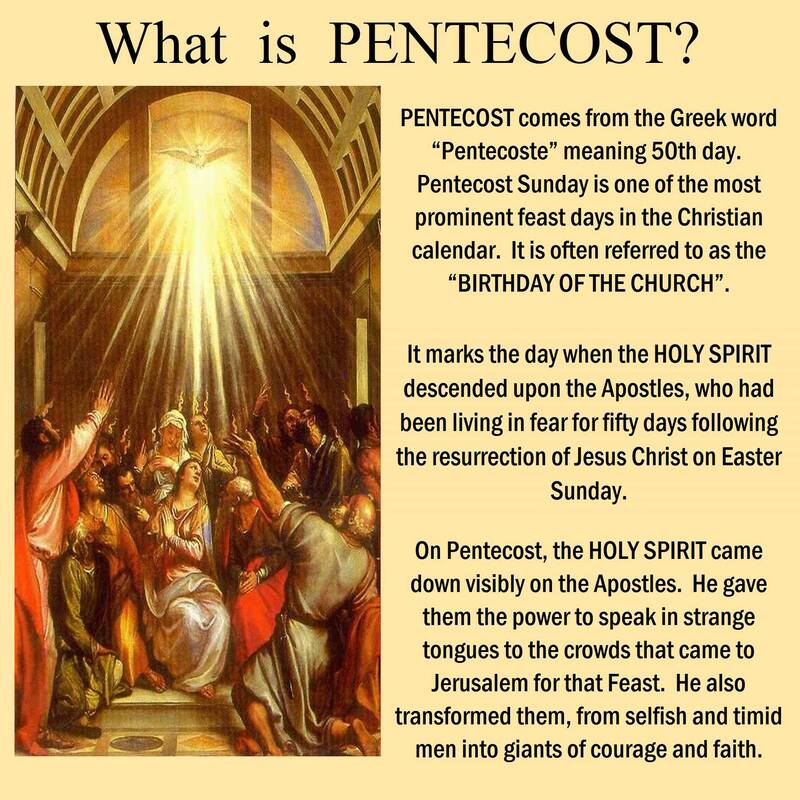

Through it, with the prompting of the Holy Spirit,

we find our way to God in Christ and learn to walk

with Him.

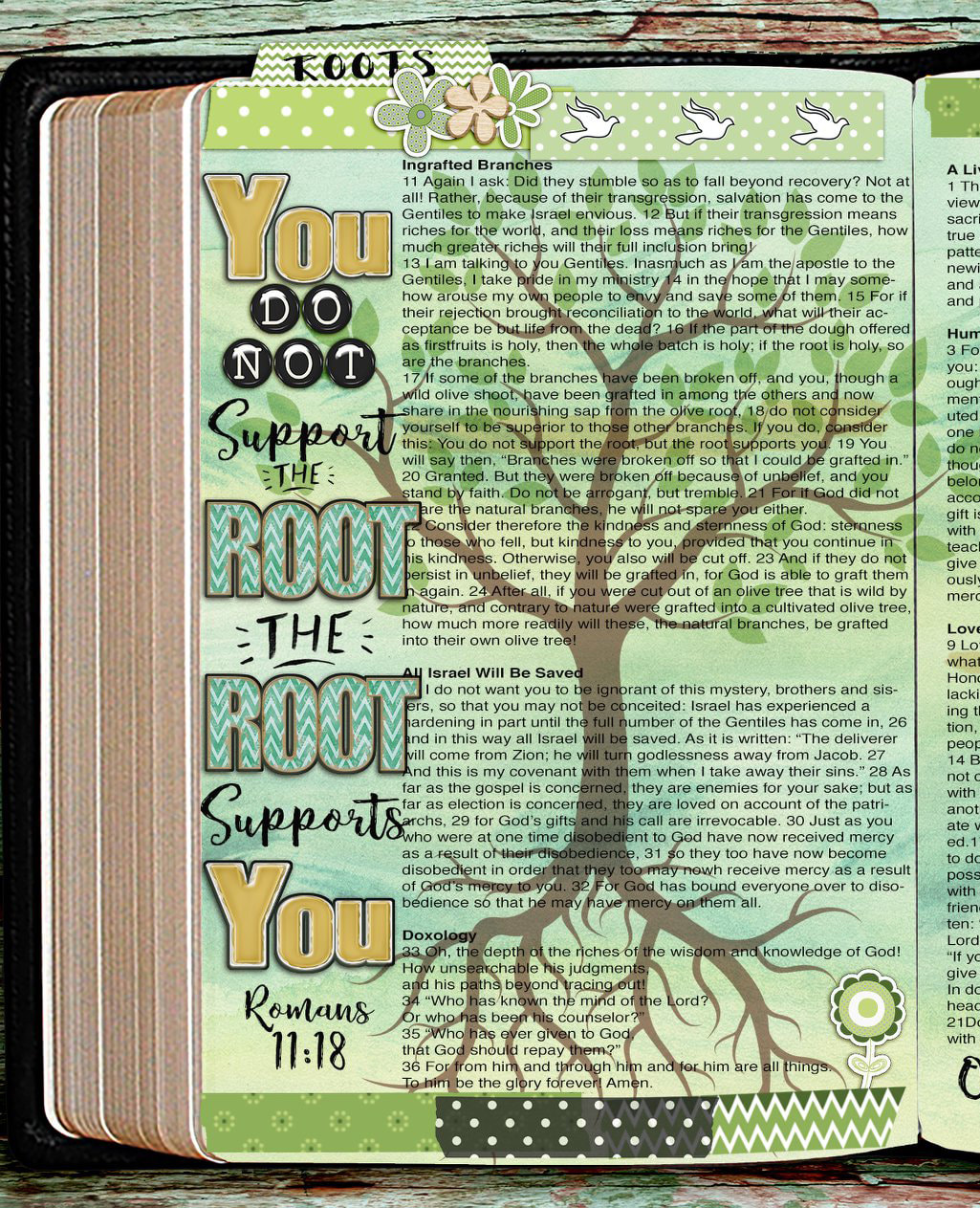

Paul was responsible for bringing Christianity

to Ephesus, Corinth, Philippi, and Thessalonica.

"Paul saw Jesus' resurrection as ushering in the eschatological time foretold by biblical prophets in which the pagan 'Gentile' nations would turn from their idols and embrace the one true God of Israel (e.g., Zechariah 8:20-23),

and Paul saw himself as specially called by God to declare God's eschatological acceptance of the Gentiles and summon

them to turn to God."

The main concern of Paul's writings on Jesus' role and

salvation by faith

is not the individual conscience of human sinners

and their doubts about being chosen by God or not,

but the problem of the inclusion of

Gentile (Greek)Torah-observers into God's covenant.

As Gentiles began to convert from Paganism to early Christianity, a dispute arose among Jewish Christian leaders as to whether or not Gentile Christians

needed to observe all the tenets of the Law of Moses.

The inclusion of Gentiles into early Christianity

posed a problem for the Jewish identity

of some of the early Christians: the new Gentile converts

were neither required to be circumcised

nor to observe the Mosaic Law.

Observance of the Jewish commandments, including circumcision,

was regarded as a token of the membership of the Abrahamic covenant,

and the most traditionalist faction of Jewish Christians

(i.e., converted Pharisees)

insisted that Gentile converts had to be circumcised as well.

By contrast, the rite of circumcision was considered execrable and repulsive during the period of Hellenization of the Eastern Mediterranean, and was especially adversed in Classical civilization both from ancient Greeks and Romans, which instead valued the foreskin positively.

Around the same time period, the subject of Gentiles and the Torah was also debated among the Tannaitic rabbis as recorded in the Talmud.

This resulted in the doctrine of the Seven Laws of Noah,

to be followed by Gentiles, as well as the determination that

"Gentiles may not be taught the Torah."

The 18th-century Rabbi Jacob Emden was of the opinion that

Jesus' original objective, and especially Paul's, was only to convert Gentiles

to follow the Seven Laws of Noah

while allowing Jews to keep the Mosaic Law for themselves

(see also Dual-covenant theology).

Paul objected strongly to the insistence on keeping

all of the Jewish commandments, considering it a

great threat to his doctrine of

salvation through faith in Christ.

Paul left Antioch and traveled to Jerusalem to discuss his mission to the Gentiles with the Pillars of the Church.

.[Acts 15:1-19]

Describing the outcome of this meeting, Paul said that "they recognized that I had been entrusted with the gospel for the uncircumcised".[Gal 2:1–10] The Acts of the Apostles describe the dispute as being resolved by Peter's speech and concluding with a decision by James, the brother of Jesus not to require circumcision from Gentile converts. Acts quotes Peter and James as saying:

"My brothers, you are well aware that from early days God made his choice among you that through my mouth the Gentiles would hear the word of the gospel and believe. And God, who knows the heart, bore witness by granting them the Holy Spirit just as he did us.

He made no distinction between us and them,

for by faith he purified their hearts.

Why, then, are you now putting God to the test by placing on the shoulders of the disciples a yoke that neither our ancestors nor we have been able to bear? On the contrary, we believe that we are saved through the grace of the Lord Jesus, in the same way as they."

-- Acts 15:7–11"It is my judgment, therefore, that we should not make it difficult for the Gentiles who are turning to God. Instead we should write to them, telling them to abstain from food polluted by idols.

— Acts 15:19–20

While the Council of Jerusalem

was described as resulting in an agreement to allow Gentile converts exemption from most Jewish commandments, another group of Jewish Christians, sometimes termed Judaizers, felt that Gentile Christians needed to fully comply with the Law of Moses, and opposed the Council's decision. For centuries Jews had looked down upon Gentiles for their covenant relationship with God, creating a deep seated wedge of hostility between the two groups.

According to the Epistle to the Galatians chapter 2,

Peter had traveled to Antioch and there was a dispute

between him and Paul.

The Epistle does not exactly say if this happened

after the Council of Jerusalem or before it,

When Peter came to Antioch, I opposed him to his face,

because he was clearly in the wrong.

Before certain men came from James, he used to eat with the Gentiles.

But when they arrived,

he began to draw back and separate himself from the Gentiles

because he was afraid of those who belonged

to the circumcision group.

To Paul's dismay,

the rest of the Jewish Christians in Antioch sided with Peter,

including Paul's long-time associate Barnabas:

The rest of the Jews joined in this charade

and even Barnabas was drawn into the hypocrisy.

The Acts of the Apostles relates a fallout between Paul and Barnabas soon after the Council of Jerusalem, but gives the reason as the fitness of John Mark to join Paul's mission (Acts 15:36–40). Acts also describes the time when Peter went to the house of a gentile. Acts 11:1–3 says:

The apostles and the believers throughout Judea heard that the Gentiles also had received the word of God. So when Peter went up to Jerusalem, the circumcised believers criticized him and said, "You went into the house of the uncircumcised and ate with them."

This is described as having happened before the death of King Herod (Agrippa) in 44 AD, and thus years before the Council of Jerusalem

(dated c. 50).

Acts is entirely silent about any confrontation between Peter and Paul, at that or any other time.

The final parting of Peter and Paul has been a subject of Christian art, pointing to a tradition of their reconciliation.Outcome. The final outcome of the incident remains uncertain; indeed the issue of Biblical law in Christianity remains disputed.

The Catholic Encyclopedia-states:

"St. Paul's account of the incident leaves no doubt that St. Peter

saw the justice of the rebuke."

In contrast, L. Michael White's From Jesus to Christianity states: "The blowup with Peter was a total failure of political bravado, and Paul soon left Antioch as persona non grata, never again to return."

According to church tradition,

Peter and Paul taught together in Rome

and founded Christianity in that city. Eusebius cites

Dionysius, Bishop of Corinth as saying,

"They taught together in like manner in Italy,

and suffered martyrdom at the same time."

This may indicate their reconciliation.

In 2 Peter 3:16, Paul's letters are referred to as "scripture", which indicates the respect the writer had for Paul's apostolic authority. However, most modern scholars regard the Second Epistle of Peter as written in Peter's name by another author.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed