Hills and Valleys,

promises, calls, and deliverance

Discipleship for New Believers

Throughout the Old Testament in the Bible, we find what seems a confusing trend of idol worship among the Israelites, who especially struggled with the worship of Baal and Asherah (or Ashtoreth). God had commanded Israel not to worship idols (Exodus 20:3; Deuteronomy 5:7)—indeed, they were to avoid even mentioning a false god’s name (Exodus 23:13). They were warned not to intermarry with the pagan nations and to avoid practices that might be construed as pagan worship rites (Leviticus 20:23; 2 Kings 17:15; Ezekiel 11:12). Israel was a nation chosen by God to one day bear the Savior of the world, Jesus Christ.

Yet, even with so much riding on their heritage and future,

Israel continued to struggle with idol worship.

Of course, the period of the judges wasn’t the first time Israel had been tempted by idol worship. In Exodus 32, we see how quickly the Israelites gave up on Moses’ return from Mount Sinai and created an idol of gold for themselves. Ezekiel 20 reveals a summary of the Israelites’ affairs with idols and God’s relentless mercy on His children (also see 1 & 2 Samuel, 1 & 2 Kings, 1 & 2 Chronicles).

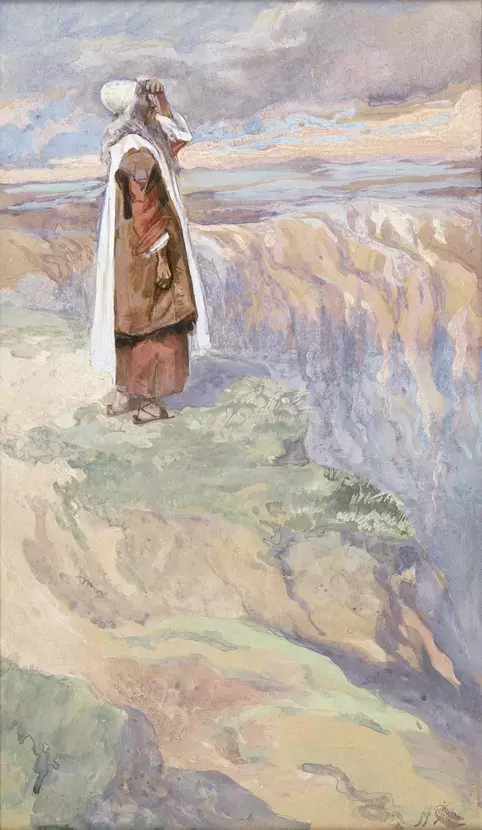

Moses is hailed as the leader of the Exodus, the one through whom God delivered His people from Egyptian slavery. To Moses God entrusted the Law. Jesus demonstrated that Moses foreshadowed His own work as the Messiah (John 3:14–15). Moses is listed in Hebrews 11 as exemplary of faith. In Deuteronomy 34 we read that God Himself buried Moses. We are also told that, “since then, no prophet has risen in Israel like Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face. . . . For no one has ever shown the mighty power or performed the awesome deeds that Moses did in the sight of all Israel” (Deuteronomy 34:10, 12). Yet Moses, for all of his blessings, was not allowed to enter the Promised Land. Why not?

In Deuteronomy 32:51–52 God gives the reason that Moses was not permitted to enter the Promised Land: “This is because . . . you broke faith with me in the presence of the Israelites at the waters of Meribah Kadesh in the Desert of Zin and because you did not uphold my holiness among the Israelites. Therefore, you will see the land only from a distance; you will not enter the land I am giving to the people of Israel.” God was true to His promise.

He showed Moses the Promised Land, but did not let him enter in.

The incident at the waters of Meribah Kadesh is recorded in Numbers 20. Nearing the end of their forty years of wandering, the Israelites came to the Desert of Zin. There was no water, and the community turned against Moses and Aaron. Moses and Aaron went to the tent of meeting and prostrated themselves before God. God told Moses and Aaron to gather the assembly and speak to the rock. Water would come forth. Moses took the staff and gathered the men. Then, seemingly in anger, Moses said to them, “Listen, you rebels, must we bring you water out of this rock?” Then Moses struck the rock twice with his staff (Numbers 20:10–11). Water came from the rock, as God had promised. But God immediately told Moses and Aaron that, because they failed to trust Him enough to honor Him as holy, they would not bring the children of Israel into the Promised Land (verse 12).

The punishment may seem harsh to us, but, when we look closely at Moses’ actions, we see several mistakes. Most obviously, Moses disobeyed a direct command from God. God had commanded Moses to speak to the rock. Instead, Moses struck the rock with his staff. Earlier, when God had brought water from a rock, He instructed Moses to strike it with a staff (Exodus 17). But God’s instructions were different here. God wanted Moses to trust Him, especially after they had been in such close relationship for so many years. Moses didn’t need to use force; he simply needed to obey God and know that God would be true to His promise.

Also, Moses took the credit for bringing forth the water. He asks the people gathered at the rock, “Must we bring you water out of this rock?” (Numbers 20:10, emphasis added). Moses seemed to be taking credit for the miracle himself (and Aaron), instead of attributing it to God. Moses did this publicly. God could not let it go unpunished and expect the Israelites to understand His holiness.

The water-giving rock is used as a symbol of Christ in 1 Corinthians 10:4. The rock was struck in Exodus 17:6, just like Christ was crucified once (Hebrews 7:27). Moses’ speaking to the rock in Numbers 20 could have been meant as a picture of prayer. Jesus was “struck” once, and He continues to provide living water to those who pray in faith to Him. When Moses angrily struck the rock, he destroyed the biblical typology and, in effect, crucified Christ again.

Moses’ punishment for disobedience, pride, and the misrepresentation of Christ’s sacrifice was steep; he was barred from entering the Promised Land (Numbers 20:12). Yet we do not see Moses complain about his punishment. Instead, he continues to faithfully lead the people and honor God.

In His holiness, God is also compassionate. He invited Moses up to Mount Nebo where He showed His beloved prophet the Promised Land before his death. Deuteronomy 34:4–5 records, “Then the Lord said to him, ‘This is the land I promised on oath to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob when I said, “I will give it to your descendants.” I have let you see it with your eyes, but you will not cross over into it.’ And Moses the servant of the Lord died there in Moab, as the Lord had said.” Moses’ failure at the rock did not negate or break his relationship with God. God continued to use the prophet and continued to love him with tenderness.

Moses and Aaron begin explaining to

the people of Israel how

Yahweh had revealed himself

and promised deliverance.

The people rejoice. But when Moses and Aaron go to Pharaoh, things get much worse. Yet Yahweh has shown himself strong against Pharaoh and has promised deliverance and Moses has learned courage. Moses now looks forward to the deliverance of the Lord.

When Moses was ready to pass on his leadership to Joshua, he commanded him to be strong and courageous. But where did Moses learn courage?

He learned it here in Egypt under the

insults and taunts of both Pharaoh and his own people.

Moses learned courage to stand.

He has gone to the elders of Israel to explain his mission as God had instructed him (Exodus 3:16). Now he goes to Pharaoh himself.

"Afterward Moses and Aaron went to Pharaoh and said, 'This is what the LORD, the God of Israel, says:

"Let my people go, so that they may hold a festival to me in the desert."'" (Exodus 5:1)

A. Moses' Early Failure (Exodus 5:1-3)

The Word of the Lord (5:1)

Moses begins with the words echoed by nearly every prophet who followed him throughout the Old Testament.

"Thus saith the LORD" (KJV)

"This is what the LORD says" (NIV)

These words resound century after century with the power of a mighty hammer (Amos 1:3, 6, etc.)

One of the lessons of Moses' leadership is that he doesn't come with his own words, but bearing God's words, which will ultimately prevail!

"... My word that goes out from my mouth:

... will not return to me empty,

but will accomplish what I desire

and achieve the purpose for which I sent it." (Isaiah 55:11)

Leaders today are tempted to come with their own words, their own message, their own spin. They quote Scripture, but that doesn't mean they are speaking the message of the Lord. Dear friends, we must listen to God for his direction to make things clear to us, then come obediently speaking the words, the message that he gives us to say.

A second lesson is patient persistence. The fulfillment of God's word didn't come immediately for Moses. He came to his adversary again and again with, "This is what the LORD says."1 Only at the end does God act. But when he acts, he acts with a power that none can withstand.

Courage in the Face of Raw Power (5:1)

A third lesson is courage. The dictionary defines "courage" as "mental or moral strength to venture, persevere, and withstand danger, fear, or difficulty."

Moses exercises great courage before Pharaoh. An 80-year-old man, who once had been adopted by one of the many daughters of a pharaoh, an alien Hebrew at that, has the temerity to tell Pharaoh what he must do. Remember, Egypt was not a democracy but a totalitarian state where, at Pharaoh's word, a man who did not please him could be struck down and killed.

Courage is required of leaders. When Moses commissions his successor Joshua, he says:

"The LORD himself goes before you

and will be with you;

he will never leave you nor forsake you.

Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged." (Deuteronomy 31:8)

I don't know about you, dear friend, but many times I have been both afraid and discouraged. God help me! As did Moses, we must find our courage in the Lord's promise that he will go with us and that he will teach us what to say. Then we must act!

Pharaoh's Response (Exodus 5:2)

Pharaoh's response to Moses' message is abrupt and proud:

"Who is the LORD, that I should obey him and let Israel go? I do not know the LORD and I will not let Israel go." (Exodus 5:2)

You speak of the LORD, Yahweh, says Pharaoh, but I don't know him and have no obligation to obey him. These defiant words against the Lord will come back to bite Pharaoh as Moses' staff and later the Ten Plagues serve as the powerful proof of Yahweh's presence with his people. God's words roll like waves to answer Pharaoh's arrogance as Moses announces the plagues upon Egypt:

- Plague of Blood: "By this you will know that I am the LORD." (7:17)

- Plague of Flies: "... so that you will know that I, the LORD, am in this land." (8:22)

- Plague of Hail: "... so you may know that the earth is the LORD's." (9:14, 29)

- Plague on the Firstborn: "Then you will know that the LORD makes a distinction...." (11:7)

A Three-Day Pilgrimage in the Desert (Exodus 5:3)

Pharaoh says "No," but Moses persists, saying to Pharaoh what the Lord tells him to say (Exodus 3:18):

"Then they said, 'The God of the Hebrews has met with us. Now let us take a three-day journey3 into the desert to offer sacrifices4 to the LORD our God, or he may strike us with plagues or with the sword.'" (5:3)

In verse 1, the phrase, "hold a festival" (NIV), "celebrate a festival" (NRSV), "hold a feast" (KJV) is ḥāgag,5 from which derives Arabic hajj, the word used for Muslims' pilgrimage to Mecca.

Harrison notes:

"Work-journals belonging to the New Kingdom period have furnished, among other reasons for absenteeism, the offering of sacrifices by workmen to their gods, and in view of the widespread nature of animal cult-worship in the eastern Delta region it is not in the least unrealistic to suppose that the Hebrews could request, and expect to receive, a three-day absence from work in order to celebrate their own religious feast in the Wilderness without at the same time provoking Egyptian religious antagonism."

But for the Hebrew slaves to ask to leave their jobs for a three-day feast was unacceptable to Pharaoh. God had hardened his hard heart.

B. Discouragement and the Lord's Instruction (Exodus 5:4-7:7)Blame the Leader (Exodus 5:4-21)

Pharaoh blames Moses and Aaron for threatening a work stoppage. He retaliates "that same day" (5:6) by requiring the Israelites to work even harder.

The sun-dried mud bricks the Israelites were making were commonly used to build houses, palaces, and temples. Bricks were made of soil and water mixed with chopped straw that gave the bricks additional strength. The mud mixture was poured into a frame-like mold. The rectangular mud brick was then tapped from the frame and left to dry in the sun.

Pharaoh commands:

"You are no longer to supply the people with straw for making bricks; let them go and gather their own straw. But require them to make the same number of bricks as before; don't reduce the quota." (5:8)

In the process, Pharaoh turns the Israelite foremen8 , who are employed by the Egyptian slave-masters, against Moses. If the Israelites don't meet the daily quota of bricks, the foremen are beaten. Now they come accusing Moses:

"When they left Pharaoh, they found Moses and Aaron waiting to meet them, and they said, 'May the LORD look upon you and judge you! You have made us a stench9 to Pharaoh and his officials and have put a sword in their hand to kill us.'" (5:20-21)

This is so typical of what leaders face. When something goes wrong, blame the leader, especially when the leader took an action that precipitated the calamity. Of course, Pharaoh is at fault, not Moses, but Moses takes the heat.

Perhaps you've seen this at work. When a pastor has to rebuke a person in the church, the retaliation is to blame the leader for something -- whether it is legitimate or not doesn't matter. Now, the leader is so busy trying defend himself that he loses sight of the mission and the opponent wins. The blame game is a diversion tactic.

Blaming God (Exodus 5:22-23)

And Moses falls for this tactic, at least initially. Moses follows the same pattern as the people and blames God himself.

"Moses returned to the LORD and said, 'O Lord, why have you brought trouble10 upon this people? Is this why you sent me? Ever since I went to Pharaoh to speak in your name, he has brought trouble upon this people, and you have not rescued11 your people at all.'" (5:22-23)

According to Moses, "You [Yahweh] have brought trouble upon this people." This sounds so like us! If I hadn't done what you told me, Lord, none of this would have happened. It's your fault, God!

What we forget is that the job of a leader is not to be liked or even to be understood. The job of a leader is to act for God to accomplish God's will on earth. It is often a thankless job fraught with brutal criticism.

If we quit when the going gets rough, if we don't persist in faith, we won't see what God will do to resolve the issue. We begin in obedience to God, and we must not falter along the way. As Moses quieted the people on the edge of the Red Sea:

"Do not be afraid. Stand firm and you will see the deliverance the LORD will bring you today.... The LORD will fight for you; you need only to be still." (Exodus 14:13-14)

"We want each of you to show this same diligence to the very end, in order to make your hope sure. We do not want you to become lazy, but to imitate those who through faith and patience inherit what has been promised." (Hebrews 6:11-12)

The Lord Encourages Moses (Exodus 6:1-8)

But Moses is not yet ready to quiet the people; God must quiet him. What follows is a passage where God reminds Moses of what he had already said: that Pharaoh's heart would be hardened and that "because of my mighty hand he will let them go" (Exodus 6:1). God reminds Moses of his covenant with the patriarchs.

"I have remembered my covenant," he says. "I will redeem you with an outstretched arm and with mighty acts of judgment" (6:6b)

The word "redeem" here is gāʾal, "redeem, avenge, revenge, ransom, do the part of a kinsman." It refers to the responsibilities of a next of kin to rescue family members from difficulty, redeem them from slavery, avenge them when they have been mistreated, etc.13 Thus Abraham raises a private army to rescue his nephew Lot who had been kidnapped (Genesis 14) and Boaz acts as kinsman-redeemer for Ruth and Naomi, the widows of his kinsman (Ruth 2:20). Yahweh is the kinsman-redeemer to Israel, fulfilling his covenant obligations made to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob centuries before.

The Lord Commands Moses (Exodus 6:9-13)

Moses reported this to the Israelites, but they did not listen to him because of their discouragement and cruel bondage." (Exodus 6:9)

Even Moses' own people won't listen to him! Moses is moping. But God doesn't quit talking to Moses. He commands him to act! Observe the dialog:

"Then the LORD said to Moses, 'Go, tell Pharaoh king of Egypt to let the Israelites go out of his country.'

But Moses said to the LORD, 'If the Israelites will not listen to me, why would Pharaoh listen to me, since I speak with faltering lips14 ?'

Now the LORD spoke to Moses and Aaron about the Israelites and Pharaoh king of Egypt, and he commanded them to bring the Israelites out of Egypt." (6:10-13)

Notice: God won't take "no" for an answer. The Lord says, "Go tell Pharaoh." Moses says, "He won't listen to me." Now the Lord commands Moses and Aaron. "Commanded" (NIV), "gave them a charge" (KJV, cf. NRSV) is ṣāwâ,"command, charge," used of instruction of a father to a son, a farmer to his laborers, and of a king to his servants. The word reflects a society where a leader is in a position to command the people and to expect their obedience.

Sometimes, dear friends, we get stubborn and God needs to tell us, in no uncertain terms, what we must do. There is no argument that we can win against God. If you are a leader for God, then he expects you to follow his instructions, no matter how hard. It's not a good sign when he needs to tell you the equivalent of, "Because I'm the mother, that's why!"

God has taken Moses and Aaron to the "woodshed" for a whipping. But finally, to their credit, they obey.

"Moses and Aaron did just as the LORD commanded them. Moses was eighty years old and Aaron eighty-three when they spoke to Pharaoh." (7:6-7)

How does God deal with his reluctant leader Moses? By command, but also by reasoning with him, encouraging him, and helping him to see the vision ahead of time of what God will do. When Moses can see it with his eye of faith, then he can act on God's behalf and be a leader.

Q1. (Exodus 7:6-7) Why did Moses blame God for his troubles? Why do you think Moses and Aaron are so stubborn? Was it fear? Was it unbelief? Or both, perhaps? Why does God have to command Moses and Aaron?

http://www.joyfulheart.com/forums/index.php?showtopic=1038

I Will Harden Pharaoh's Heart (Exodus 7:1-6)

Following a genealogical insertion in 6:14-25 (see Appendix 3), the narrative continues:

"But I will harden Pharaoh's heart, and though I multiply my miraculous signs and wonders in Egypt, he will not listen to you. Then I will lay my hand on Egypt and with mighty acts of judgment I will bring out my divisions, my people the Israelites." (Exodus 7:3-4)

Theologians have spent lots of time discussing Pharaoh's hard heart. Was it hard initially? If God hardened it, is Pharaoh really responsible for his actions? The word "hardened" (ḥāzaq16) appears 12 times in Exodus 4-14. Notice three different statements:

- Yahweh hardens Pharaoh's heart (active) -- Exodus 4:21; 7:3, 13; 9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10, 14:4, 8, (17)

- Pharaoh's heart is hardened (passive) -- Exodus 7:13, 14, 22; 8:19; 9:7, 35

- Pharaoh hardens his own heart (reflexive) -- Exodus 8:15, 32; 9:34

In fact, Pharaoh is an unrepentant sinner from the start. Harris observes,

"All of God's hardening of an obstinate sinner was judicial and done that God's deliverance should be the more memorable."

Certainly, Pharaoh is guilty of sin and rebellion against God. This instance is similar to how God treats hardened sinners elsewhere. In Romans 1, for example, Paul notes that it is because of their gross sins, "God gave them over" to even greater sin (Romans 1:24, 26).

C. God's Increasing Judgment on Egypt (Exodus 7:8-11:10)

The Plagues upon Egypt (Exodus 7:8-11:9)

Now come the Ten Plagues against Egypt. The word "plague" is maggēpâ, "blow, pestilence," from nāgap, "to strike."18 God himself is striking Egypt with his own hand. Of course, since our study is primarily on Moses the leader, we can't analyze each plague in detail.

There have been various attempts to explain these plagues as naturally occurring phenomena, either seasonal or cyclical events occurring in nature. Unfortunately, any explanation we might offer is mere speculation, not scientific fact. Of course, God may have used nature to bring these judgments. But they are presented as miracles, so, unless we believe that miracles are impossible, or that these are merely natural phenomena that seemed like miracles to primitive, unsophisticated minds, we'll refrain. However, observe three things:

- The Egyptians saw the God of the Israelites as the cause of the judgments.

- The plagues did not fall on the Israelites, only on the Egyptians.

- The timing was exquisite.

The plagues may have occurred over a period as long as six months.- These are the plagues:

- Blood (7:14-24).20 The blood of the plague makes the Nile's water undrinkable and kills the fish (7:21) -- a major industry along the Nile.

- Frogs (8:1-15). Frogs in Egypt were associated with the god Hopi and the goddess Heqt, who assisted at childbirth, and were thus a fertility symbol.21 For all the frogs to die and rot must have been seen as a defeat of the Egyptian gods.

- Gnats (8:16-19). "Gnats" (NIV, NRSV), "lice" (KJV) is Hebrew kēn. We don't really know what kind of insect is intended by the word. "Fleas" or "sandflies" have been suggested, but more likely it refers to "mosquitoes."22

- Flies (8:20-32). "Swarm [of flies]" in verse 20 is literally ʿārōb, "swarm" ("mixture," from incessant involved motion).23 We're not told what kind of flies they were, but perhaps flies attracted by the decaying frogs. The Septuagint translates the word as kynomuia, "dog-fly," perhaps our modern gadfly or Monarch fly, with a painful bite.24This plague it is described as a "severe25 swarm." Whatever it was, it must have been pretty awful, since Pharaoh is induced to send the Israelites away, though he relents.

- Livestock (9:1-7). Since many varieties of "livestock" (NIV), "cattle" (KJV)26 were considered sacred animals by the Egyptians, this plague "on your horses and donkeys and camels and on your cattle and sheep and goats" (9:3), was a direct blow against Egypt's gods. The statement that "all the cattle of Egypt died" (9:6) is sometimes contrasted with the fact that the Egyptians still had livestock prior to the plague of hail (9:19). Childs comments, "The discrepancy is not a serious one, since the narrative style should not be overtaxed."27

- Boils (9:8-12). "Ashes of the furnace" that Moses and Aaron threw into the air would be black and fine like soot. "Festering boils" (NIV, NRSV) consists of two words, translated by Childs as "boils breaking out into pustules."28 It sounds pretty ugly.

- Hail (9:13-35). Hailstones have been measured as large as 8 inches in diameter29 and can be terribly destructive. I once had a rental car pockmarked by hail in an intense storm near St. Cloud, Minnesota. The storm that devastated Egypt was much more severe, destroying crops in the fields and trees, as well as livestock left in the open.

- Locusts (10:1-20). Locusts are still a dreaded pest in areas bordering the desert. In Amos 7:1-3 and Joel 1:1-7 they are seen a terrible figure of God's judgment. Our text reads, "They covered all the ground until it was black. They devoured all that was left after the hail" (10:15a).

- Darkness (10:21-29). This darkness is so intense that it can be "felt."30 There is speculation that this must have been a sandstorm, but if this were the case, I think the narrator would have said so. Instead of the whirling sand, it is the darkness that is so awful.

- Firstborn (11:1-10; 12:29-32). The final plague is the death of the firstborn son as well as the firstborn of livestock throughout Egypt. We will examine this plague further in Lesson 3.

Moses Staff- At God's direction, Moses and Aaron use their staffs to work miracles, both before the Israelites and before Pharaoh. Sometimes it is Moses' staff that is employed; other times it is Aaron's. They seem interchangeable, since Aaron is acting as Moses' spokesman.

"Staff" (NIV, NRSV), "rod" (KJV) is maṭṭeh, "staff, rod, shaft" from the verb nāṭâ, "extend, stretch out." The staff is closely associated with the hand31 in Exodus, and was used as a support when travelling, a common walking stick that was probably carried by every man. The staff could be used as a weapon, probably much like the medieval quarter-staff (Psalm 2:9; 23; 4; 89:32; Isaiah 10:24; 11:4), and was used for such everyday tasks as to thresh herbs (Isaiah 28:27) and count sheep (Ezekiel 20:37). A staff carried some value (Genesis 38:18), probably since suitable trees were somewhat scarce. It could also represent the authority of a leader (Numbers 17:1-11) as a kind of scepter (Psalm 110:2; Jeremiah 48:17).

At the conclusion of Yahweh's first revelation to Moses at the burning bush, God says:

"But take this staff in your hand so you can perform miraculous signs with it.... So Moses took his wife and sons, put them on a donkey and started back to Egypt. And he took the staff of God in his hand." (Exodus 4:17, 20)

This "staff of God" (Exodus 4:20; 17:9) figures in miracles both in Egypt and during their sojourn in the wilderness.

The Staff and Ancient Concepts of Magic

Ive wondered, though, if the "staff of God" is used in Moses' ministry as a kind of magical object -- an ancient magic wand. Some Christians are troubled by concepts of the miraculous efficacy of objects, such as the bones of saints (relics), anointing oil for healing (Mark 6:13; James 5:14), and "prayer cloths" (Acts 19:12). How do we understand Moses' rod?

Magic was widespread in the ancient near east as an attempt to understand, control, or manipulate the divine realm.33 But rather than seeking to manipulate God to their own ends, Moses and Aaron use their rods at God's explicit direction, as their obedient response to a specific situation, perhaps as a visible symbol of God's authority.

Why does Jesus sometimes lay on hands for healing, and at other times speak a word or use spittle? We don't know. We do know, however, that sometimes God directs us to use specific physical objects in the pursuit of his purposes. This understanding seems to characterize the biblical description of Moses' rod better than assigning it to the category of magic.

The Ten Plagues of Egypt—also known as the Ten Plagues, the Plagues of Egypt, or the Biblical Plagues—are described in Exodus 7—12. The plagues were ten disasters sent upon Egypt by God to convince Pharaoh to free the Israelite slaves from the bondage and oppression they had endured in Egypt for 400 years. When God sent Moses to deliver the children of Israel from bondage in Egypt, He promised to show His wonders as confirmation of Moses’ authority (Exodus 3:20). This confirmation was to serve at least two purposes: to show the Israelites that the God of their fathers was alive and worthy of their worship (Exodus 6:6–8; 12:25–27) and to show the Egyptians that their gods were nothing (Exodus 7:5; 12:12; Numbers 33:4).

The Israelites had been enslaved in Egypt for about 400 years and in that time had lost faith in the God of their fathers. They believed He existed and worshiped Him, but they doubted that He could, or would, break the yoke of their bondage. The Egyptians, like many pagan cultures, worshiped a wide variety of nature-gods and attributed to their powers the natural phenomena they saw in the world around them. There was a god of the sun, of the river, of childbirth, of crops, etc. Events like the annual flooding of the Nile, which fertilized their croplands, were evidences of their gods’ powers and good will. When Moses approached Pharaoh, demanding that he let the people go, Pharaoh responded by saying, “Who is the Lord, that I should obey his voice to let Israel go? I know not the Lord, neither will I let Israel go” (Exodus 5:2). Thus began the challenge to show whose God was more powerful.

The first plague, turning the Nile to blood, was a judgment against Apis, the god of the Nile, Isis, goddess of the Nile, and Khnum, guardian of the Nile. The Nile was also believed to be the bloodstream of Osiris, who was reborn each year when the river flooded. The river, which formed the basis of daily life and the national economy, was devastated, as millions of fish died in the river and the water was unusable. Pharaoh was told, “By this you will know that I am the LORD” (Exodus 7:17).

The second plague, bringing frogs from the Nile, was a judgment against Heqet, the frog-headed goddess of birth. Frogs were thought to be sacred and not to be killed. God had the frogs invade every part of the homes of the Egyptians, and when the frogs died, their stinking bodies were heaped up in offensive piles all through the land (Exodus 8:13–14).

The third plague, gnats, was a judgment on Set, the god of the desert. Unlike the previous plagues, the magicians were unable to duplicate this one and declared to Pharaoh, “This is the finger of God” (Exodus 8:19).

The fourth plague, flies, was a judgment on Uatchit, the fly god. In this plague, God clearly distinguished between the Israelites and the Egyptians, as no swarms of flies bothered the areas where the Israelites lived (Exodus 8:21–24).

The fifth plague, the death of livestock, was a judgment on the goddess Hathor and the god Apis, who were both depicted as cattle. As with the previous plague, God protected His people from the plague, while the cattle of the Egyptians died. God was steadily destroying the economy of Egypt, while showing His ability to protect and provide for those who obeyed Him. Pharaoh even sent investigators (Exodus 9:7) to find out if the Israelites were suffering along with the Egyptians, but the result was a hardening of his heart against the Israelites.

The sixth plague, boils, was a judgment against several gods over health and disease (Sekhmet, Sunu, and Isis). This time, the Bible says that the magicians “could not stand before Moses because of the boils.” Clearly, these religious leaders were powerless against the God of Israel.

Before God sent the last three plagues, Pharaoh was given a special message from God. These plagues would be more severe than the others, and they were designed to convince Pharaoh and all the people “that there is none like me in all the earth” (Exodus 9:14). Pharaoh was even told that he was placed in his position by God, so that God could show His power and declare His name through all the earth (Exodus 9:16). As an example of His grace, God warned Pharaoh to gather whatever cattle and crops remained from the previous plagues and shelter them from the coming storm. Some of Pharaoh’s servants heeded the warning (Exodus 9:20), while others did not. The seventh plague, hail, attacked Nut, the sky goddess; Osiris, the crop fertility god; and Set, the storm god. This hail was unlike any that had been seen before. It was accompanied by a fire which ran along the ground, and everything left out in the open was devastated by the hail and fire. Again, the children of Israel were miraculously protected, and no hail damaged anything in their lands.

Before God brought the next plague, He told Moses that the Israelites would be able to tell their children of the things they had seen God do in Egypt and how it showed them God’s power. The eighth plague, locusts, again focused on Nut, Osiris, and Set. The later crops, wheat and rye, which had survived the hail, were now devoured by the swarms of locusts. There would be no harvest in Egypt that year.

The ninth plague, darkness, was aimed at the sun god, Re, who was symbolized by Pharaoh himself. For three days, the land of Egypt was smothered with an unearthly darkness, but the homes of the Israelites had light.

The tenth and last plague, the death of the firstborn males, was a judgment on Isis, the protector of children. In this plague, God was teaching the Israelites a deep spiritual lesson that pointed to Christ. Unlike the other plagues, which the Israelites survived by virtue of their identity as God’s people, this plague required an act of faith by them. God commanded each family to take an unblemished male lamb and kill it. The blood of the lamb was to be smeared on the top and sides of their doorways, and the lamb was to be roasted and eaten that night. Any family that did not follow God’s instructions would suffer in the last plague. God described how He would send the destroyer through the land of Egypt, with orders to slay the firstborn male in every household, whether human or animal. The only protection was the blood of the lamb on the door. When the destroyer saw the blood, he would pass over that house and leave it untouched (Exodus 12:23). This is where the term Passover comes from. Passover is a memorial of that night in ancient Egypt when God delivered His people from bondage. First Corinthians 5:7 teaches that Jesus became our Passover when He died to deliver us from the bondage of sin. While the Israelites found God’s protection in their homes, every other home in the land of Egypt experienced God’s wrath as their loved ones died. This grievous event caused Pharaoh to finally release the Israelites.

By the time the Israelites left Egypt, they had a clear picture of God’s power, God’s protection, and God’s plan for them. For those who were willing to believe, they had convincing evidence that they served the true and living God. Sadly, many still failed to believe, which led to other trials and lessons by God. The result for the Egyptians and the other ancient people of the region was a dread of the God of Israel. Even after the tenth plague, Pharaoh once again hardened his heart and sent his chariots after the Israelites. When God opened a way through the Red Sea for the Israelites, then drowned all of Pharaoh’s armies there, the power of Egypt was crushed, and the fear of God spread through the surrounding nations (Joshua 2:9–11). This was the very purpose that God had declared at the beginning. We can still look back on these events today to confirm our faith in, and our fear of, this true and living God, the Judge of all the earth.

Distinction between Egypt and the Israelites

The Lord says to Pharaoh through Moses,

"I will make a distinction between my people and your people."

(Exodus 8:23)

The plagues which fall on the Egyptians don't directly affect the Israelites, who live in a particular part of Egypt, the land of Goshen. This distinction appears explicitly in the:

- Plague of Flies (Exodus 8:22-23)

- Plague on Livestock (Exodus 9:4-6)

- Plague of Hail (Exodus 9:26)

- Plague of Darkness (Exodus 10:23)

- Plague on the Firstborn (Exodus 11:7)

But this selectivity of the effects of the plagues may have occurred in the other plagues, too, since the narrator emphasizes the effect on the Egyptians and doesn't mention any effects on the Israelites whatsoever.

God doesn't punish his people with the punishments of their oppressors.

Leadership Lessons

As I reflect on Moses' leadership during these plagues, several leadership lessons occur to me.

1. The Leader Must Confront When Necessary

Moses is asked -- no, commanded -- to confront the most powerful person on the face of the earth:

Pharaoh, king of Egypt.

I don't know about you, but I don't like confrontations. I've learned, however, that leaders must confront when necessary, or their organization will lose its sense of direction and unity.

Not confronting, when one needs to,

hardly ever makes the situation better.

And putting it off only makes the situation worse.

Good parents confront their children when they're behaving badly in order to 'correct' them. Undisciplined children are the result of parents who refuse to confront, rebuke, and correct.

Do you have a situation that you need to confront

to be a good leader under God?

Ask God to give you wisdom and courage.

Then do what you need to do.

That's the job of a leader.

In the Gospels, you'll see that

-Jesus did a lot of confronting -

of the people he healed, of the people who opposed him,

and of his errant disciples.

Jesus was not a laissez-faire leader, but one who lovingly,

but firmly confronted.

So did the Apostle Paul.

These are examples for us.

Q2. Why is it so difficult for some congregation leaders to confront people? What fears in this regard does a leader face?

How can confrontation and rebuke be a good thing?

What happens when we refuse to confront when we should?

2. The Leader Must Deal with Criticism and Pressure

Ive tried to imagine the kind of pressure Moses was under.

After Moses' first encounter with Pharaoh, the Israelites were punished by being required to find their own straw without any reduction in their quota of bricks.

Now Moses' own people accuse him

of upsetting the status quo for something new and negative.

Then Moses stands before Pharaoh who heaps abuse on him and his God.

It's surprising that Pharaoh doesn't just kill Moses at the outset,

but to do so would probably have caused riots among the Hebrews and threatened the stability of Pharaoh's oppressive regime.

How well did Moses sleep during this period?

How many emissaries did he receive from the Israelites pleading with him to cease and desist and go back where he came from?

How many representatives of Pharaoh did he entertain who were trying to find a compromise solution so that Egypt would not be destroyed? How many threats against his life did he have to deal with?

The period of the Ten Plagues took place over months and months. In hindsight, we know that there were ten plagues,

but neither Moses nor the Egyptians knew how long

the plagues would last.

So how did Moses sustain himself?

Through faith in the word that the Lord had given him that Yahweh would deliver Israel from Egypt. Through all the ups and downs of this period, Moses remains steady, trusting in the word of the Lord.

So must we.

3. The Leader Must Know When to Compromise -- and When Not To

As I read these chapters, I see Pharaoh trying to negotiate a settlement for less than Moses has demanded. That Pharaoh, king of Egypt, feels he must negotiate at all, demonstrates the threat he feels. See his tactics:

- During the Plague of Flies, Pharaoh offers to allow sacrifice to God "within the land" or "in the wilderness, provided you do not go very far away," but Moses does not compromise. (8:25-27, 32).35

- Prior to the Plague of Locusts, Pharaoh seems to be willing to let the men sacrifice, but not the women and children. Moses does not compromise (10:10).

- During the Plague of Darkness, Pharaoh seems willing to allow all the people to go and worship, but they must leave their flocks and herds behind. Moses does not compromise (10:24-26).

A lesser leader than Moses would have been tempted to accept a compromise. After all, leaders, both in churches and in statehouses, use compromise as a way to keep from stalemate and to accomplish the business that must be accomplished. You don't always get everything you want. "Half a loaf is better than none," goes the saying. Politics is the art of compromise.

Of course, leaders must learn to compromise if we want to move the congregation or body forward. Leaders must do what needs to be done to achieve the greater purpose.

But there are times when we leaders must not compromise.

That is when God has been clear.

Moses has been charged with obedience to God, and only through his obedience will God bring about the truly impossible -- the deliverance of the Israelites from Egypt through the Red Sea as well as the destruction of the Egyptian army.

To Moses' credit, he continues to be faithful to the word, the vision that God has given him. And since he is faithful, he receives the promised reward (Hebrews 10:35).

"By faith he left Egypt, not fearing the king's anger; he persevered because he saw him who is invisible." (Hebrews 11:27, NRSV)

Leader, don't abandon the vision

God has given you!

Q3. Why didn't Moses accept Pharaoh's compromises?

4. The Leader Must Know that the Battle Is the Lord's

Finally, and most important, the leader must know the real protagonists in the battle. In order to correct something, we need to identify the cause- and that might be a hard truth to swallow.

This is not really a battle between Moses and Pharaoh at all.

The Apostle Paul reminds us:

"For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the powers, against the world forces of this darkness, against the spiritual forces of wickedness in the heavenly places."

(Ephesians 6:12, NASB)

But it is very easy for us leaders to think that this is a battle of wills between us and a human opponent. When we leaders confront evil people, we sometimes end up demonizing our opponents in what may appear to be a personal battle of wills. But Jesus tells us to love our enemies!

So it is important to recognize that this is a contest not between Moses and Pharaoh. Rather, it is a contest between the God of the Hebrews and the gods of Egypt -- including Pharaoh himself. It is a battle between following

god's will and design, or going the opposite direction of it. Following the true God of Israel, or idols.

'You shall not make for yourselves an idol, nor any image of anything that is in the heavens above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: you shall not bow yourself down to them, nor serve them, for I, Yahweh your God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children, on the third and on the fourth generation of those who hate me, and showing loving kindness to thousands of those who love me and keep my commandments."

– Exodus 20:4-6 (WEB)

If Rameses II was the pharaoh during the Exodus, it is interesting to observe that he had been deified, declared a god, when he was 30 years old, only half-way through his long 66-year reign.

He was one of the false gods of Egypt.

Moses does not speak to Pharaoh as he might as a former prince of Egypt. Moses speaks for Yahweh, the God of the Hebrews. And as God's spokesman, his words are powerful. A mere human would quail to say such things to the most powerful monarch on earth, but as fearful Moses may have felt on the inside, he speaks God's words with clarity. For example:

"This is what the LORD, the God of the Hebrews, says: Let my people go ... or this time I will send the full force of my plagues against you and against your officials and your people, so you may know that there is no one like me in all the earth.... You still set yourself against my people and will not let them go." (9:13b-14, 17)

"This is what the LORD, the God of the Hebrews, says: 'How long will you refuse to humble yourself before me? Let my people go, so that they may worship me.'" (10:3)

Finally, after the Ninth Plague, Pharaoh in his anger makes a personal threat against Moses.

"'Get out of my sight! Make sure you do not appear before me again! The day you see my face you will die.'

'Just as you say,' Moses replied, 'I will never appear before you again.'" (10:28-29)

But the threat against Moses is a threat against Moses' God, since Moses speaks for God. Now God brings the tenth and final devastating plague against Egypt, and it is Pharaoh's own son who dies.

It seems that leaders from

generation to generation

must relearn this lesson:

the battle is the Lord's!

- Moses: "The LORD will fight for you." (Exodus 14:14)

- David to Goliath and the Philistines: "All those gathered here will know that it is not by sword or spear that the LORD saves; for the battle is the LORD'S, and he will give all of you into our hands." (1 Samuel 17:47)

- Jahaziel: "Listen, King Jehoshaphat and all who live in Judah and Jerusalem! This is what the LORD says to you: 'Do not be afraid or discouraged because of this vast army. For the battle is not yours, but God's." (2 Chronicles 20:14)

- Zechariah: "This is the word of the LORD to Zerubbabel: 'Not by might nor by power, but by my Spirit,' says the LORD Almighty." (Zechariah 4:6)

These must be battles of faith and of prayer, not mere human strategy and clever words. If you want to be a leader like Moses, then you must learn to listen like Moses, trust like Moses, and lead like Moses.

We are not our own. We have been bought with a price (1 Corinthians 6:20).

We are his- And he will defend us if we represent him clearly and forthrightly as we lead.

Q4. Why do we so often mistake the human enemy for the spiritual enemy?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed