Since the

fall of man,

the basis of salvation has

always been

the

death of Christ.

No one, either prior to the cross or since the cross,

would ever be saved without that one pivotal

event in the history of the world.

Christ’s death paid the penalty for past sins of Old Testament

saints and future sins of

New Testament saints.

The requirement

for salvation has always been

faith.

The object of one’s faith

for salvation has always

been God.

The psalmist wrote,

“Blessed are all who take

refuge in him”

(Psalm 2:12). Genesis 15:6

tells us

that Abraham believed God and

that was enough for God to

credit it to

him for righteousness

(see also Romans 4:3-8). The Old Testament sacrificial system did not take away sin, as Hebrews 10:1-10 clearly teaches. It did, however,

point to the day when the

Son of God would shed

His blood for the sinful human race.

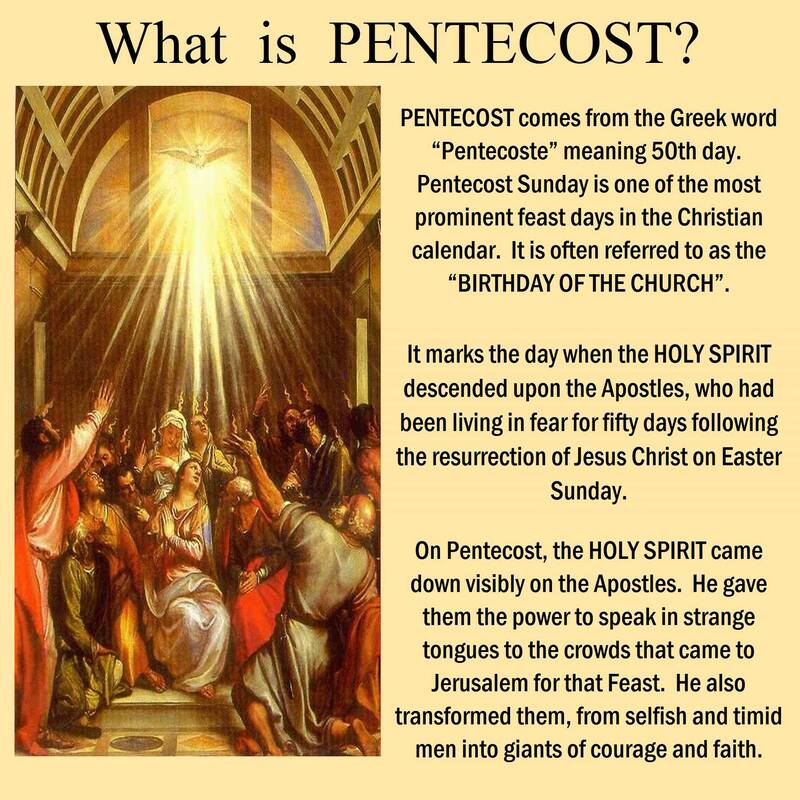

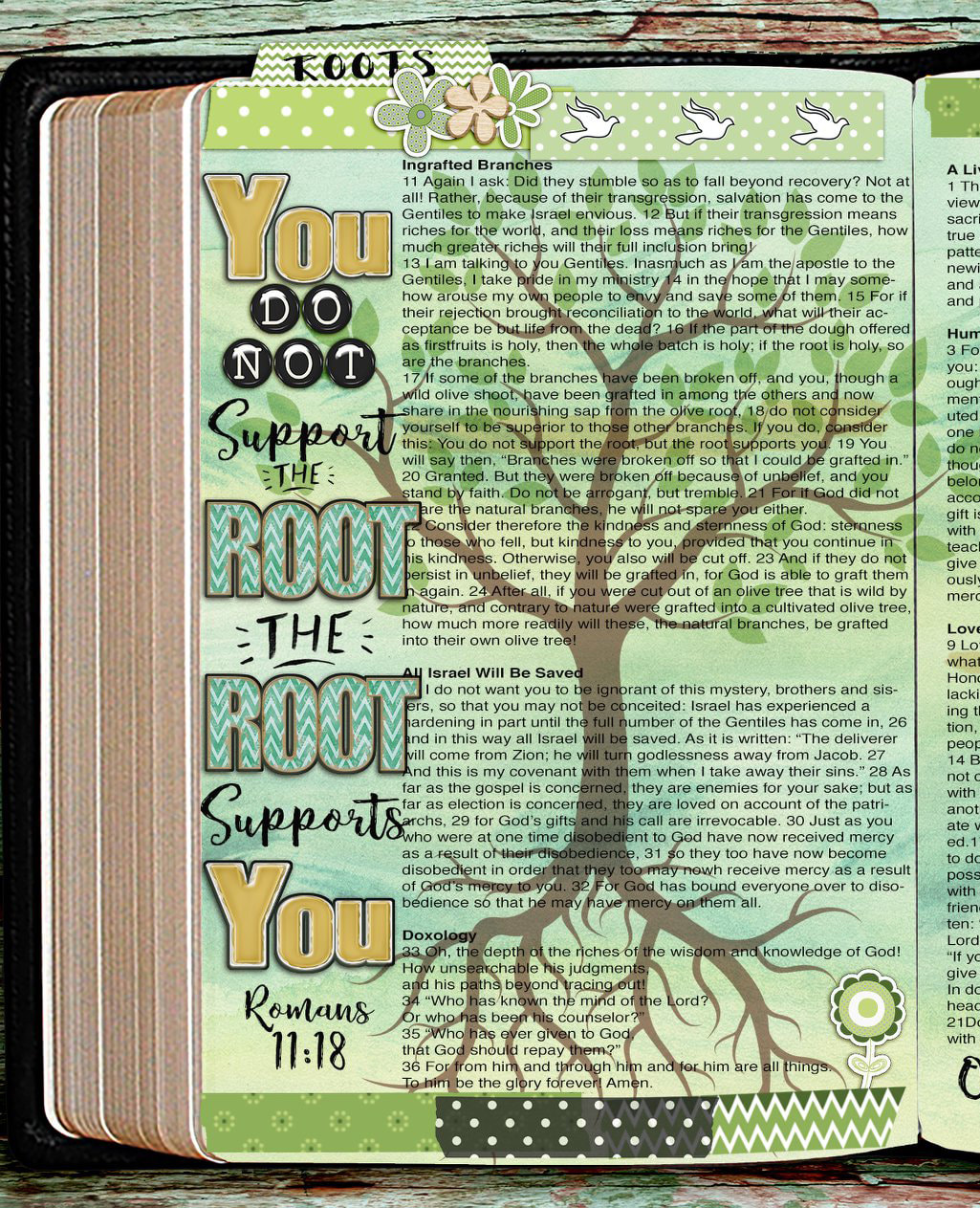

What has changed through the ages is the content of a believer’s faith. God’s requirement of what must be believed is based on the amount of revelation He has given mankind up to that time. This is called progressive revelation. Adam believed the promise God gave in Genesis 3:15 that the Seed of the woman would conquer Satan. Adam believed Him, demonstrated by the name he gave Eve (v. 20) and the Lord indicated His acceptance immediately by covering them with coats of skin (v. 21). At that point that is all Adam knew, but he believed it.

Abraham believed God according to the promises and new revelation God gave him in Genesis 12 and 15. Prior to Moses, no Scripture was written, but mankind was responsible for what God had revealed. Throughout the Old Testament, believers came to salvation because they believed that God would someday take care of their sin problem. Today, we look back, believing that He has already taken care of our sins on the cross (John 3:16; Hebrews 9:28).

What about believers in Christ’s day, prior to the cross and resurrection? What did they believe? Did they understand the full picture of Christ dying on a cross for their sins? Late in His ministry, “Jesus began to explain to his disciples that he must go to Jerusalem and suffer many things at the hands of the elders, chief priests and teachers of the law, and that he must be killed and on the third day be raised to life” (Matthew 16:21-22). What was the reaction of His disciples to this message? “Then Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him. ‘Never, Lord!’ he said. ‘This shall never happen to you!’” Peter and the other disciples did not know the full truth, yet they were saved because they believed that God would take care of their sin problem. They didn’t exactly know how He would accomplish that, any more than Adam, Abraham, Moses, or David knew how, but they believed God.

Today, we have more revelation than the people living before the resurrection of Christ; we know the full picture. “In the past God spoke to our forefathers through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed heir of all things, and through whom he made the universe” (Hebrews 1:1-2). Our salvation is still based on the death of Christ, our faith is still the requirement for salvation, and the object of our faith is still God. Today, for us, the content of our faith is that Jesus Christ died for our sins, He was buried, and He rose the third day (1 Corinthians 15:3-4).

The First Council of Constantinople occurred in AD 381 in the city of the same name (modern Istanbul, Turkey). It is considered the second of the Ecumenical Councils, after Nicea in 325. At the Council of Constantinople, Christian bishops convened to settle several doctrinal disputes prompted by unrest in the religious leadership of the city. While not as memorable as the Council of Nicea, the council dealt a fatal blow to Arianism, clarified the language used to describe the Trinity, and sharpened the distinctions between the Eastern and Western branches of the church.

The immediate motivation behind calling the first Council of Constantinople was a series of controversies. The Council of Nicea had met more than fifty years prior to settle the Arian controversy, a debate over whether or not Jesus was fully divine. Despite the council’s nearly 300-to-2 decision rejecting Arianism, the view persisted and continued to cause division among Christians. Constantinople itself was considered an “Arian” city until a new Emperor, Theodosius I, attempted to forcibly replace its church leaders with non-Arians.

This attempted purge did not go over well, and further unrest ensued. Theodosius attempted to install Gregory Nazianzus as Bishop of Constantinople. However, before Gregory could be formally consecrated, a rival group broke into the cathedral and attempted to consecrate Maximus the Cynic, instead. Their consecration ritual was interrupted by an angry mob, leading Theodosius to ask Pope Damasus for advice. Damasus’s order was for Theodosius to call a meeting of bishops who would formally reject Maximus and settle (again) the Arian controversy.

True to form, the beginning of the Council of Constantinople was marred by controversy. The man first selected to preside over the Council, Meletius of Antioch, died soon after the council opened. Gregory was then elected to lead the discussions, but a late-arriving contingent of bishops opposed both Gregory’s leadership of the council and his installment as Bishop of Constantinople. This led to an argument that threatened to derail the entire process. Gregory offered to resign both offices, a solution that ended the controversy and allowed the council to continue.

Once under way,

the Council of Constantinople

again strongly denounced Arianism.

Council members also discussed the

hierarchy of bishops,

rules for bringing heretics back into the church,

and disciplinary issues

among church leaders.

Central to these discussions were

careful applications of

correct terminology when

discussing the Trinity.

In particular, it extended the language of the Nicene Creed

to more precisely reflect the orthodox position.

Here is the Nicene Creed with the changes made by the

Council of Constantinople in brackets:

We believe in one God,

the Father Almighty, Maker [of heaven and earth],

and of all things visible and invisible,

and in one Lord Jesus Christ,

the [only-begotten] Son of God, begotten of the Father

[before all worlds],

Light of Light,

very God of very God, begotten, not made,

being of one substance with the Father;

who for us men, and for our salvation, came down [from heaven],

and was incarnate [by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary],

and was made man;

he [was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, and] suffered,

[and was buried], and the third day he

rose again, [according to the Scriptures, and]

ascended into heaven, [and sitteth on the right hand of the Father];

from thence he shall come [again, with glory],

to judge the quick and the dead;

[whose kingdom shall have no end].

And in the Holy Ghost, [the Lord and Giver of life,

who proceedeth from the Father,

who with the

Father and the Son together is worshiped and glorified,

who spake by the prophets.

In one holy catholic and apostolic Church;

we acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins;

we look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come. Amen.]

Much as a prior emperor, Constantine, had called the Council of Nicea to determine the boundaries of “orthodox” Christianity, Theodosius I intended the Council of Constantinople to unify Roman Christians under a common core of belief. To some extent, this goal was achieved, in that several doctrinal points were clarified. Arianism began to decline and eventually withered away.

At the same time, the Council of Constantinople heightened the growing divide between the Eastern and Western Churches. One of the council’s declarations proclaimed that “the Bishop of Constantinople, however, shall have the prerogative of honor after the Bishop of Rome, because Constantinople is New Rome.” This generated disagreement over the relative importance of the five major Christian jurisdictions: Rome, Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Jerusalem. When the Great Schism occurred centuries later, one of the primary disagreements was the hierarchy of Rome and Constantinople.

In AD 553, the fifth ecumenical council of the Christian church assembled by decree of Emperor Justinian and led by Eutychus, patriarch of Constantinople. Known as the Second Council of Constantinople, Pope Vigilius of Rome, who had been summoned to Constantinople against his will, showed his displeasure by taking sanctuary in a church for more than seven months. Pope Vigilius eventually ended his protest by formally ratifying the council’s verdicts in February of the following year.

Fourteen anathemas, or condemnations, were decreed by the Second Council of Constantinople. At stake was the biblical doctrine of the dual nature of the Lord Jesus Christ. The Bible teaches Jesus was fully God (John 1:1; 8:58) yet fully man (John 1:14). This duality of nature in one person is known as the hypostatic union. To deny Jesus’ divine nature is heretical; to deny His human nature is equally heretical. The Second Council of Constantinople issued their fourteen anathemas in order to silence the false teachers who refused to accept the essential biblical teachings surrounding the person and nature of the Lord Jesus Christ.

Convinced strict religious conformity was necessary to keep the Byzantine Empire intact, Emperor Justinian convoked the Second Council of Constantinople when factions of the church could not agree upon Christ Jesus’ dual natures. In his campaign for religious conformity, Emperor Justinian had pagans baptized against their will, closed schools whose teachings were contrary to Christianity, and fiercely persecuted a sect known as the Montanists. Montanists believed the Holy Spirit had given their leader, Montanus, new revelation. This “new revelation” dealt with personal conduct rather than doctrine. In a belief Montanus was a heretic, Emperor Justinian vigorously opposed his followers. As to Pope Vigilius’ opposition to the Second Council of Constantinople, Emperor Justinian threatened to prevent the pope from returning to Rome unless he agreed to the fourteen anathemas.

Nestorianism, a false belief that Christ was two separate persons, one human and one divine, had been adopted by some church leaders. This breech in orthodox Christology was expressed in writings that came to be known as the Three Chapters: the writings of Theodore of Mopsuestia, certain works of Theodoret of Cyrus, and the letter of Ibas to Maris. At the previous Council of Chalcedon, the Nestorian writings had been rebuked but not condemned outright. At the Second Council of Constantinople, the assembly reaffirmed their belief in Christ’s two natures while condemning those who believed there were “two Sons or two Christs.”

Also in error was monophysitism. The monophysites believed that Christ Jesus had only one nature, a teaching propagated by Cyril of Alexandria. Empress Theodora, herself a monophysite, had urged Justinian to call a council as a political maneuver to discredit the rival Nestorians. Justinian, who believed religious conformity would bring the empire back to its glory days, agreed to Theodora’s request by summoning the church’s leaders to Constantinople in 553.

In the end, erroneous teachings surrounding the person and nature of the Lord Jesus were condemned at the Second Council of Constantinople. Quite possibly, Emperor Justinian’s motives for calling the council were as political as they were theological, but the assembly stood firm against heretical teachings. Some may consider the disagreements among the various factions in Constantinople as theological hair-splitting, but the subject of Christology is hardly a peripheral issue. Every cult and ism, past and present, begins with a false understanding of the person and nature of God. Our finite minds cannot completely fathom the depth of Christ’s character, but the plain teaching of Scripture is that He is fully God and fully man. Ultimately, the fourteen anathemas issued by the Second Council of Constantinople were justified and necessary.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed