In Christianity, a martyr is a person considered

to have died

because of their testimony

for

Jesus or faith in Jesus.

In years of the early church, stories depict this often occurring

through death by sawing, stoning, crucifixion, burning at the stake

or other forms of torture and capital punishment.

The word martyr comes from the Koine word

μάρτυς, mártys,

which means

"witness" or "testimony"

At first, the term applied to Apostles.

Once Christians started to

undergo persecution,

the term came to be applied to those

who suffered hardships for their faith.

Finally, it was restricted to those who had been

killed for their faith.

The early Christian period before Constantine I was

the "Age of Martyrs". "

Early Christians venerated martyrs as powerful intercessors,

and their utterances were

treasured as inspired by the Holy Spirit."

In western Christian art, martyrs are often shown holding a palm frond

as an attribute,

representing the victory of spirit over flesh,

and it was widely believed that a picture of a

palm on a tomb meant that a martyr was buried there.

Jesus, King of Martyrs

The Apostle Paul taught that Jesus was "obedient unto death,"

a 1st century Jewish phrasing for self-sacrifice in Jewish law. Because of this, some scholars believe Jesus' death was Jewish martyrdom.

Jesus himself said he had come to fulfill the Torah. The Catholic Church calls Jesus the "King of Martyrs" because, as man, he refused to commit sin unto the point of shedding blood

The Early Church; See also: Persecution of Christians in the New Testament

Stephen is the first martyr reported in the New Testament,

accused of blasphemy and stoned

by the Sanhedrin under the Levitical law.

Towards the end of the 1st century, the

martyrdom of both Peter and Paul is reported

by Clement of Rome in 1 Clement.

The martyrdom of Peter is also alluded to in various writings written between 70 and 130 AD, including in John 21:19; 1 Peter 5:1; and 2 Peter 1:12–15. The martyrdom of Paul is also alluded to in 2 Timothy 4:6–7. While not specifying his Christianity as involved in the cause of death, the Jewish historian Josephus reports that James, the brother of Jesus, was stoned by Jewish authorities under the charge of law breaking, which is similar to the Christian perception of Stephen's martyrdom as being a result of stoning for the penalty of law breaking. Furthermore, there is a report regarding the martyrdom of James son of Zebedee in Acts 12:1–2, and knowledge that both John and James, son of Zebedee, ended up martyred, appears to be reflected in Mark 10:39.

Judith Perkins has written that many ancient Christians believed that

"to be a Christian was to suffer,"

partly inspired by the example of Jesus. The lives of the martyrs became a source of inspiration for some Christians, and their relics were honored. Numerous crypts and chapels in the Roman catacombs

bear witness to the early veneration for those champions

of freedom of conscience.

Special commemoration services, at which the holy Sacrifice were offered over their tombs gave rise to the time honoured custom of consecrating altars by enclosing in them the relics of martyrs.

The Bible does not say how the apostle Paul died.

Writing in 2 Timothy 4:6–8, Paul seems to be anticipating his soon demise:

"For I am already being poured out as a drink offering, and the time of my departure has come.

I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race,

I have kept the faith.

Henceforth there is laid up for me the crown of righteousness,

which the Lord, the righteous judge, will award to me on that Day,

and not only to me but

also to all who have loved his appearing.”

Second Timothy was written during Paul’s second

Roman imprisonment in AD 64—67.

There are a few different Christian traditions in regards to how Paul died,

but the most commonly accepted one comes from the writings of Eusebius,

an early church historian.

Eusebius claimed that Paul was beheaded

at the order

of the Roman emperor Nero or one of his subordinates.

Paul’s martyrdom occurred shortly after much of

Rome

burned in a fire—an event that

Nero blamed on the Christians.

It is possible that the apostle Peter was martyred

around the same time, during this period of early

persecution of Christians.

The tradition is that Peter was crucified upside down and that

Paul was beheaded due to the fact that Paul was a Roman citizen

(Acts 22:28),

and Roman citizens were normally exempt from crucifixion.

For all indications, he died for his faith.

We know he was ready to die for Christ

(Acts 21:13),

and Jesus had predicted

that Paul would

suffer much for the name of Christ

(Acts 9:16).

Based on what the Book of Acts recorded of Paul’s life,

we can assume he died

declaring the gospel of Christ,

spending his last breath

as a witness to the truth that sets men free

(John 8:32).

In Corinth, in the early fifties of the first century A.D., Paul faced opponents within the Church who felt that the way to understand God and the vicissitudes of mortality was through the use of philosophy or, as Paul puts it, the “enticing words of man’s wisdom” (1 Corinthians 2:4). It is in response to this situation in Corinth that Paul makes the following statement in 1 Corinthians 2:1–2: “

And I, brethren, when I came to you,

I came not with excellency of speech or of wisdom,

declaring unto you the testimony of God.

For I determined not to know any thing among you,

save Jesus Christ, and him crucified.”

In that single declaration, Paul spotlights for us

the

very core of his personal ministry.

The only way to understand God and mortality is to

come

to know that Jesus Christ was and is

the

Redeemer of the world and that

He alone had the power to change lives

by

redeeming individuals

from the power of sin and death.

Now, Paul’s witness of these things was

not some abstract, theoretical premise; rather,

it was grounded in

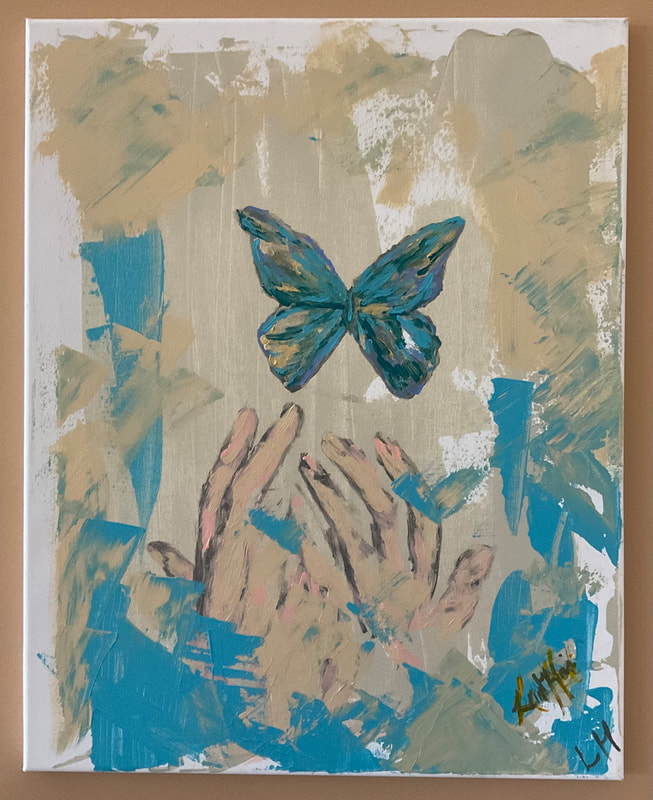

his own personal metamorphosis.

nothing in Creation knows this

better than the butterfly.

He had “spiritually been born of God”

and had

experienced the “mighty change” of heart of which Alma speaks

(Alma 5:14).

Paul wanted everyone he came in contact with to

have the same type of experience.

As a result, he dedicated his life to bringing the

message of “Jesus Christ, and him crucified”

to the world.

The sheer volume of Paul’s letters that have survived antiquity make this

apostle to the Gentiles

our greatest single New Testament personality

to bear testimony

of

the power of Christ and His atoning sacrifice.

Paul’s testimony of Christ is multidimensional and there are numerous aspects that we could discuss here, but the limits of time demand that I be selective.

I propose, therefore, to focus briefly on just three

areas of Paul’s testimony of Christ: first,

his testimony that Christ changes lives; second,

his

testimony of the Resurrection;

and third, his

testimony of the faith of Christ.

Christ Changes LivesI love the following statement from President Ezra Taft Benson:

“The Lord works from the inside out.

The world works from the outside in. . . .

The world would mold men by changing their environment.

Christ changes men, who then change their environment.

The world would shape human behavior,

but

Christ can change human nature. . . .

Yes, Christ changes men, and changed men can change the world.”

Paul’s conversion to Christ

is a prime example of what President Benson is talking about.

He was able to teach and bear witness to the world of the power of Christ to change lives because he had personally experienced that metamorphosis.

He knew firsthand about both the cost and the implications of such a metamorphosis, and he also knew the impact that it could bring—not just for the individual, but also for the Church and the

community as a whole.

Before his conversion, by his own confession, Paul considered himself to be “the least of the apostles” because he “persecuted the church of God”

(1 Corinthians 15:9; see also Galatians 1:13).

In fact, he wrote to Timothy that he was the chief of sinners

(see 1 Timothy 1:15).

The events on the road to Damascus, however, proved to be a dramatic course correction for this young persecutor. We all know the basic events that took place on that day, but there are some elements that Acts leaves unclear, and we have to look to other sources for clarification. For example, the text does not indicate why the Lord chose to appear to Paul and not to others. Certainly Paul was not the only individual who persecuted the Church.

The fact that Christ told Ananias that Paul

was a “chosen vessel”

strongly indicates that the vision was the result of foreordination.

Elder Bruce R. McConkie has noted the following: “Nothing [Paul] had done on earth qualified him for what was ahead;

but his native spiritual endowment, nurtured and earned

in [the] pre-existence, prepared him for the coming ministry.

Paul was the quintessential example of what is possible

when a person turns to Christ.

Recognizing the importance of Paul’s experience

for

all would-be Christians,

Luke records not just one, but three accounts of Paul’s conversion

(see Acts 9:3–20; 22:5–16; 26:12–19).

In that vision,

Paul saw, for the first time, the resurrected Christ.

Using language reminiscent of the First Vision, Paul declares the following to King Agrippa:

"At midday, O king, I saw in the way a light from heaven, above the brightness of the sun, shining round about me and them which journeyed with me. And when we were all fallen to the earth, I heard a voice speaking unto me, and saying in the Hebrew tongue, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me? it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks” (Acts 26:13–14). Saul was not the only person to see the light, but he was the only one to hear Christ’s voice

(see Acts 22:9; JST, Acts 9:7).

The scriptures are also silent about why this vision was so life-changing for Paul; after all, an angel appearing to Laman and Lemuel did little to change their behavior (see 1 Nephi 3:28–31). Elder Neal A. Maxwell suggests that Paul “may have already been ‘in a preparation’ [see Alma 32:6], perhaps brooding and pondering before his great vision.” President David O. McKay suggests that some of that preparation may have occurred as Paul spent a week traveling to Damascus. He indicates that Paul may have used this time to reflect on recent events. “Perhaps the shining face of the dying Stephen and the martyr’s last prayer began to sink more deeply into his soul than it had done before.”

Perhaps, he continues,

"little children’s cries for their parents whom Saul had bound began to pierce his soul more keenly, and make him feel miserably unhappy as he looked forward to more experiences of that kind in Damascus. Perhaps he wondered whether the work of the Lord, if he were really engaged in it, would make him feel so restless and bitter.” Some kind of reflection must have been going on in Paul’s mind because his immediate response to Christ’s rebuke for “kick[ing] against the pricks” was the

submissive question, “Lord, what wilt thou have me to do?”

(Acts 9:5–6; see also 22:10).

Can I suggest to you that it was that submission that allowed

the power of Christ to work within Paul.

Never again could he doubt or question

the

centrality of Christ for mankind’s salvation.

Never again could he doubt or question the importance of

Christ vis-a-vis the law of Moses. Never again could he doubt or question what was possible when people turned their life over to Christ.

What is interesting to me here is that all of the detailed accounts of this event are recorded in Acts and not in Paul’s personal epistles. The two times that he does briefly mention the vision are in Galatians 1:15–17 and 1 Corinthians 15:8–11. In Galatians his testimony is simple, direct, and concise: “The one who set me apart from my mother’s womb and who called me through his grace was pleased to reveal his son in me so that I might preach him among the Gentiles” (author’s translation). Likewise, in 1 Corinthians 15 while testifying of the Resurrection, Paul declares, “And last of all he was seen of me also, as of one born out of due time” (v. 8). Surely in these instances Paul could elaborate considerably on his personal experience to help the Saints better appreciate Christ’s power, but he chooses not to. That raises the question, why not? Why doesn’t he give a more detailed description of his conversion in his personal letters? As dramatic as that event was, why doesn’t Paul use it as his clarion call to the Saints? Surely the impact of such a story would have stirred the hearts of all who heard it. Even King Agrippa, after hearing of these events, said, “Almost thou persuadest me to be a Christian” (Acts 26:28).

Perhaps we find a clue to Paul’s reasoning in his reference to it in 1 Corinthians 15. Paul uses the Greek word ektroma, which the King James translators rendered as “one born out of time.” This is an interesting word; we find it used nowhere else in the New Testament and it is uncommon even in Greek literature. At least on one level, we must understand this word as being parallel with the next verse where Paul says that he is “the least of the apostles,” but perhaps there is an additional way that we can understand it. As one scholar notes, “the decisive feature [of ektroma] is the abnormal time of birth and the unfinished form of the one thus born.” [6] This vision was definitely untimely, given Paul’s history as a persecutor of the Church. It was certainly not something that he had earned. I am particularly interested in the latter half of this statement: the “unfinished form” of the birth. Let me suggest that by choosing this particular word, Paul wanted to indicate to his readers that the real change in his life came not from the spectacular visitation per se—the vision began the birthing process, but it could only be completed by the subsequent day to day struggle to live as a Christian, to follow the life of the Savior, and to apply the redemption that comes only from the Atonement in his life. Years after the road to Damascus experience, Paul told the Philippians that he was not “already perfect, “but that he “pressed forward . . . because Christ Jesus has made me his own” (RSV, Philippians 3:12). The visitation was the catalyst for Paul’s spiritual metamorphosis but was not the sustaining force behind it. This change in emphasis does not lessen the power of Christ to change lives, it just moves the conversion process from the dramatic to more subtle experiences with the Spirit (see 1 Kings 19:9–12). Elder Maxwell reminds us that although “God is certainly present in thedramatic, spiritual ‘about faces,’ such as occurred on the road to Damascus, . . . He is also [present] in the smaller course corrections.” [7] It is certainly these “smaller course corrections” that Paul knew were pivotal for his personal metamorphosis and would be the driving force behind how his readers experienced the power of Christ in their lives. That is where he puts his emphasis in his personal letters.

But if that vision was not what Paul saw as the center of transformation, what was? The answer for us, I think, is much more subtle. It is manifest in Paul’s use of a simple phrase—a phrase he uses seventy-four times in his epistles. Paul wants very much for his readers and all those with whom he comes in contact to be “in Christ.” It is as we seek this covenantal relationship that the real transformation takes place in our lives. We must be clear that Paul testifies that being “in Christ” is a process, not just an event. It is a process that begins before an individual joins the Church and continues through the spectrum of mortality and even unto death and resurrection. Thus, to the Ephesians, Paul testifies that even the Gentiles who were “far off’ from Christ can be “in Christ” as they are brought near “by the blood of Christ” (2:13). In other words, as nonmembers begin the process of coming to Christ, they also begin the process of being “in Christ.” That process continues even after they join the Church. Paul describes the members of the Church in Corinth as being “babes in Christ” (1 Corinthians 3:1).

Even though these Saints were members of the Church,

they still had not reached a level of spiritual maturity that

would allow Paul to speak to them of spiritual matters.

Lastly,

even those who have died can be “in Christ.”

Paul promises those who

die “in Christ shall rise first”

(1 Thessalonians 4:16),

or, in other words, shall be a

part of the first resurrection of the just.

Why is it so important to Paul that his readers strive to be “in Christ”? Precisely because as they struggle to do so, they change; qualitatively they become very different from whom they once were. President Benson taught us that “when you choose to follow Christ, you choose to be changed.” That concept is what George McDonald portrayed in the following parable, which was made famous by C. S. Lewis.

"Imagine yourself as a living house. God comes in to rebuild that house. At first, perhaps, you can understand what He is doing. He is getting the drains right and stopping the leaks in the roof and so on: you knew that those jobs needed doing and so you are not surprised. But presently he starts knocking the house about in a way that hurts abominably and does not seem to make sense. What on earth is He up to? The explanation is that He is building quite a different house from the one you thought of—throwing out a new wing here, putting on an extra floor there, running up towers, making courtyards. You thought you were going to be made into a decent little cottage: but He is building a palace. He intends to come and live in it Himself.”

Paul taught the same principle this way:

"If any man be in Christ, he is a new creature:

old things are passed away;

behold, all things are become new”

(2 Corinthians 5:17; see also Colossians 3:10).

Alma the Younger, whose life in many ways parallels Paul’s, said that we become new creatures when we are “born again; yea, born of God, changed from [our] carnal and fallen state,

to a state of righteousness, being redeemed of God, becoming

his sons and daughters” (Mosiah 27:25).

As “sons [and daughters] of God,” Paul testifies that we become “joint-heirs with Christ” (Romans 8:14, 17), thus inheriting all that the Father has.

Can you think of anything more ennobling than this goal?

Let me summarize.

Paul’s metamorphosis into a “new creation”

may have been initiated by his vision of Christ,

but the process of being “in Christ” and thus becoming

a “new creature” was a constant struggle for him.

But the struggle

was not so that he could make himself a “new creation”;

it was so he could be “in Christ” and thus allow Christ

to make that change in him.

I love the example that Paul gives us of what was possible in his life,

and I love the way that he spent his life

trying to lift people’s sights so that they could also

understand how Christ could change their lives

if they would only let Him in.

Christ’s Resurrection

Lest anyone should miss the central importance of the Resurrection in Paul’s teachings, he begins with the following statement

: “For I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures; and that he was buried, and that he rose again the third day according to the scriptures”

(1 Corinthians 15:3–4).

The phrase that the King James translators render as “first of all” (en protois) can also be translated as the “most important things.”

Thus, Paul makes it patently clear that the two most important elements of his teaching, that which he has taught from the very beginning, are the Atonement and Resurrection.

In other words, without the Resurrection his preaching of the Atonement would be incomplete. In fact, he declares that “if Christ be not risen, then is our preaching vain, and your faith is also vain”

(1 Corinthians 15:14),

because “if in this life only we have hope in Christ,

we are of all men most miserable”

(1 Corinthians 15:19).

The implications of Paul’s witness here are twofold.

First, it is precisely because of

Paul’s hope in the Resurrection

that he is willing to “stand . . . in jeopardy

every hour,” “die daily,”

and fight “with beasts at Ephesus”

(1 Corinthians 15:30–32).

Because Paul understood

the doctrine of Christ’s resurrection,

he could view the vicissitudes

of life

from an

eternal rather than a mortal perspective.

Repeatedly, President Boyd K. Packer has taught

us that

"true doctrine, understood, changes

attitudes and behavior.”

Second, Paul taught that without the Resurrection, nothing

else in the Christian message, even the Atonement, makes sense.

C. S. Lewis reminds us that

“the Resurrection is the central theme in

every Christian sermon reported in Acts.

The Resurrection, and its consequences,

were the ‘gospel’ or good news which

the Christians brought.”

Two thousand years later, the importance of the Resurrection cannot be explained away by modern philosophies. Note how one scholar responds to such arguments: “There seems to be little hope of getting around Paul’s argument, that to deny Christ’s resurrection is tantamount to a denial of Christian existence altogether.

Yet many do so—to make the faith more palatable to ‘modern man,’

we are told. . . . What modern man accepts in its place is no longer the

Christian faith, which

predicates divine forgiveness

through Christ’s death

on his resurrection.

Nothing else is the Christian faith,

and those who reject the actuality of the resurrection of Christ

need to face the consequences of such rejection,

that they are bearing false witness against God himself.

Like the Corinthians they will have believed

in vain since faith is finally

predicated on

whether or not Paul is right on this issue.”

Lest anyone in either ancient or modern times should doubt the reality of this great event, Paul lists some of the eyewitnesses.

“And that he was seen of Cephas, then of the twelve: after that, he was seen of above five hundred brethren at once; of whom the greater part remain unto this present, but some are fallen asleep.

After that, he was seen of James; then of all the apostles. And last of all he was seen of me also” (1 Corinthians 15:5–8). Paul knew that under the Mosaic law, “in the mouth of two or three witnesses shall every word be established” (2 Corinthians 13:1; see also Deuteronomy 19:15). Clearly, those witnesses satisfied the burden of proof with regard to the Resurrection.

Thus, with the reality of Christ’s resurrection firmly established, Paul also stresses the impact that resurrection has on the rest of humanity. Although Christ was resurrected, death still rules in the world; it is still the enemy.

The power of Christ’s resurrection is not just that He overcame death,

but that He opened the doors for all of humanity.

"But now is Christ risen from the dead, and become the firstfruits of them that slept. For since by man came death, by man came also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ[note that phrase again] shall all be made alive”

(1 Corinthians 15:20–22; see also 2 Corinthians 4:14).

Death was not cheated just once by Christ’s resurrection. The beauty is that His resurrection will ultimately defeat death by enabling all to be resurrected. President Gordon B. Hinckley testified that “of all the victories in human history, none is so great, none so universal in its effect, none so everlasting in its consequences as the victory of the crucified Lord, who came forth in the resurrection that first Easter morning.”

Is it any wonder, therefore, that Paul’s declaration resounds in the minds and hearts of those who understand the majesty of Christ’s efforts on our behalf:

"O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory? . . .

Thanks be to God, which giveth us the victory through

our Lord Jesus Christ”

(1 Corinthians 15:55,57).

The second issue that Paul addresses in 1 Corinthians 15 deals with the nature of resurrected beings: “But some man will say, How are the dead raised up? and with what body do they come?” (1 Corinthians 15:35).

Paul’s response is that we will be raised with a “spiritual body”

(1 Corinthians 15:44)

Notice how in verses 36 through 38 he teaches this principle through the imagery of planted seeds: we may plant “bare grain,” but God gives it a body. But then note verse 39: “All flesh is not the same flesh: but there is one kind of flesh of men, another flesh of beasts, another of fishes, and another of birds.”

Paul follows this verse with the passage

that we often use in the Church

as a proof text for the three degrees of glory:

“There are also celestial bodies, and bodies terrestrial:

but the glory of the celestial is one,

and the glory of the terrestrial is another.

There is one glory of the sun, and another glory of the moon,

and another glory of the stars:

for one star differeth from another star in glory”

(1 Corinthians 15:40–41).

In the passage’s context, the celestial and terrestrial

bodies refer to the type of bodies that one may

receive in the Resurrection.

It would seem, therefore, that there are

differing degrees of spiritual transformation

that our bodies experience in the Resurrection.

In a 1917 conference address, Elder Melvin J. Ballard said that “those who live the laws and attain unto the glory of the celestial shall have a body” whose “fineness and texture” or “composition” shall be greater than those who inherit a lower degree of glory.

Just as there are degrees of glory that we can inherit depending upon our faithfulness, so we will inherit resurrected bodies that are

commensurate with our spirits.

Thus, Paul further testifies, although our physical bodies are sown in corruption, dishonor, and weakness, eventually they will be raised in incorruption, glory, and power. In short, our bodies may have been sown as natural bodies of flesh and blood, but because of Christ’s resurrection they are raised as spiritual bodies (see 1 Corinthians 15:42–44),

transformed so as to “bear the image of the heavenly [Christ]”

(1 Corinthians 15:49).

What a glorious doctrine the Resurrection is!

During the first century,

Paul’s testimony of Christ’s resurrection

stood as a powerful witness in an

environment that sometimes sought to

undermine its fundamental principles.

His witness is unequivocal on both the reality of

Christ’s resurrection

in the flesh and on the empowering ability to

physically resurrect and transform humanity.

As we enter the twenty-first century,

his witness continues to resound for

those who have ears to hear.

The Faith of Christ

The third and final aspect of

Paul’s witness of Christ

that I would like to briefly discuss centers on the

principle of faith.

Even though it is the

first principle of the gospel,

I think that it is a worthy conclusion to our discussion.

One of the central messages that Paul

taught the world

is that we are justified, or made righteous,

through faith in Christ.

Over the last two thousand years much has been written on this subject;

I would like here to focus on a less-discussed although

equally important aspect of Paul’s testimony.

He testifies that salvation comes not only because

of our

"faith in Christ,” but also because of the

“faith of Christ.”

Although there are seven passages that we could turn to (see Romans 3:22, 26; Galatians 2:16, 20; 3:22; Ephesians 3:12), let us concentrate on Philippians 3.

In this chapter, Paul speaks of the sacrifices he has made so that

he “may win Christ”

(Philippians 3:8).

Note what he says in verse 9:

"And be found in him, not having mine own righteousness,

which is of the law,

but that which is through the faith of Christ,

the

righteousness which is of God by faith.”

To whose faith is Paul referring here? The emphasis in this verse is not that righteousness comes through our faith in Christ,but that it comes through the faith of Christ,

Faith is not something that mortals outgrow as they spiritually mature.

The Prophet Joseph taught us that faith

is “the foundation of all righteousness,”

that it is “the principle of action in all intelligent beings,” and that

it is “the principle of power which existed in the bosom of God.”

None of these characteristics indicate

that faith is spiritually transitory or something that we outgrow. In fact, the Prophet taught that faith “is the principle by

which Jehovah [i.e., Christ] works.”

I think that Paul understood this

broader definition of faith, and that is why he talks

of the “faith of Christ.”

I believe that in the premortal existence,

it was faith that enabled the Savior to respond to the Father by saying,

“Father, thy will be done, and the glory be thine forever”

(Moses 4:2).

I believe that it was faith that enabled Christ to humble Himself,

to leave behind His exalted station,

and to condescend into mortality.

I believe that it was faith that enabled Christ to

ward off Satan’s temptations as He prepared for His mortal ministry,

and I believe that it was faith that enabled Him

in the Garden of Gethsemane to declare,

“Nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done” (Luke 22:42).

In each of these situations, faith was both a

principle of action and of empowerment.

It was faith

that Christ had in His Father and in His Father’s plan.

That is why Paul declares that our righteousness

comes because of Christ’s faith.

It is central to Paul’s testimony of Christ that

He was faithful in fulfilling His part in His Father’s plan.

Paul’s testimony to us, therefore, is that we can have faith in Christ because, ultimately, He has faith in His Father. This is not a principle that we should underestimate.

It is the foundation for Paul and his

testimony of Christ.

A Witness of Christ

The Apostle Paul is one of the great

witnesses of Christ.

Here I have only touched on three elements of Paul’s testimony, but let me suggest that we could spend a lifetime

learning about Christ from this great Apostle.

He loved the Savior, and from the instant

that he had his vision

on the road to Damascus, he spent

his life serving Him.

Let me close with the following plea from Paul that, for me,

epitomizes

his testimony of Christ:

“Who shall separate us from the

love of Christ?

shall tribulation, or distress, or persecution,

or

famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword?”

Paul had experienced all of these conditions.

He responds to his own question:

“Nay, in all these things we are

more than conquerors

through

him that loved us.

For I am persuaded, that neither death, nor life, nor angels,

nor

principalities, nor powers, nor things present, nor things to come,

nor

height, nor depth, nor any other creature,

shall be able to separate

us

from the love of God,

which is

in

Christ Jesus our Lord”

(Romans 8:35, 37–39).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed