The phrase the law and the prophets

https://youtu.be/wF0KYWKXZ0s

refers to the entire Hebrew Bible, what we call the Old Testament.

Jesus spoke of

“the law and the prophets”

multiple times,

such as when He listed the two greatest commandments

(Matthew 22:40).

In the

Sermon on the Mount,

Jesus pointed to His absolute perfection,

saying,

“Do not think that I have come to abolish

the

Law or the Prophets;

I have not come to abolish them

but to fulfill them”

(Matthew 5:17).

On the Emmaus Road,

Jesus taught two disciples

“everything written about himself

in the Scriptures,

beginning

with the

Law of Moses

and the

Books of the Prophets”

(Luke 24:27, CEV).

Clearly, all Scripture, indicated by “the law and the prophets,”

pointed to Jesus.

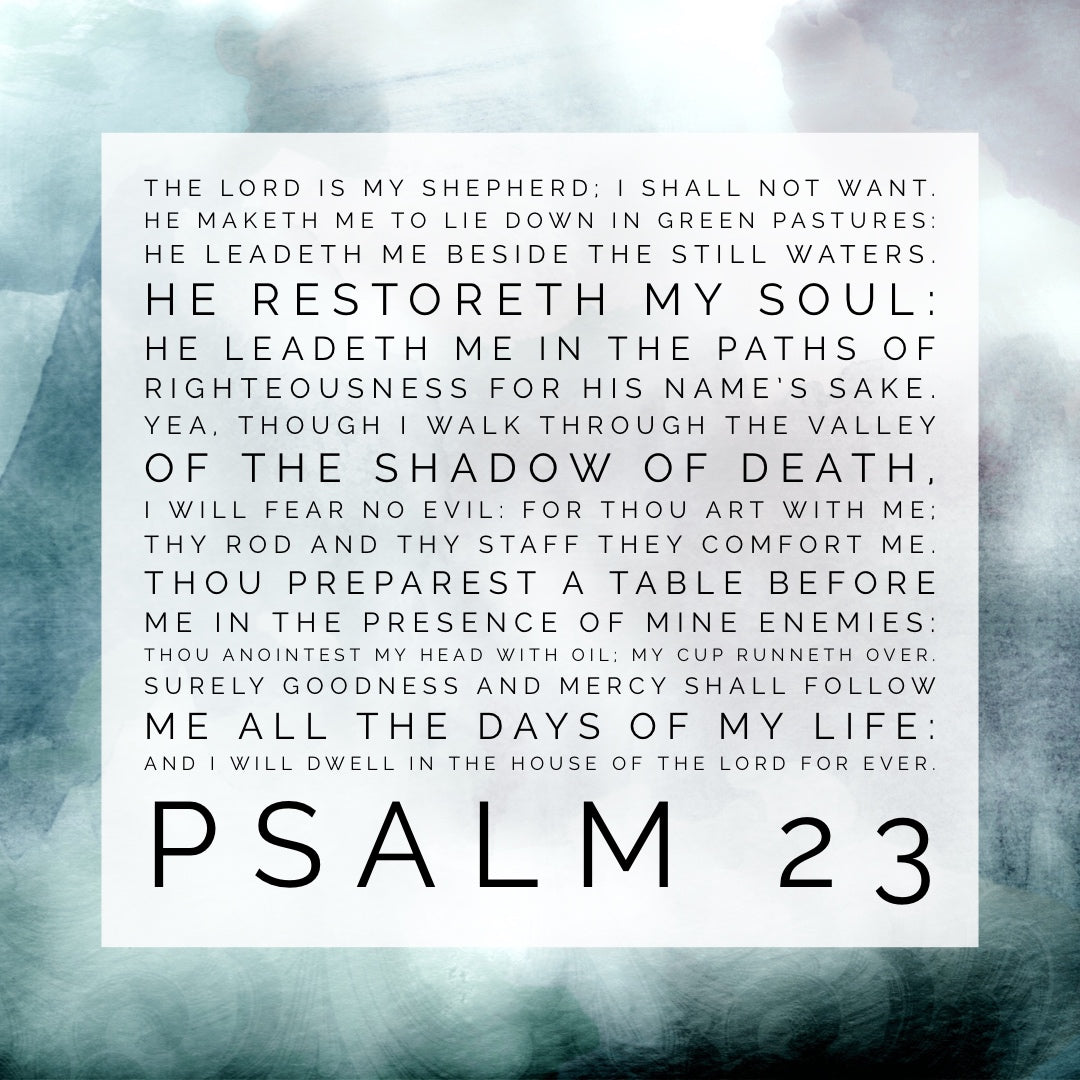

The same passage also contains a three-fold division of the Old Testament:

“the Law of Moses,

the Prophets and

the

Psalms”

(verse 44),

but the two-fold division of “the law and the prophets”

was also customary (Matthew 7:12; Acts 13:15; 24:14; Romans 3:21).

The books of the law, properly speaking, would comprise the Pentateuch: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

The prophets, in the two-fold division, would include

the rest of the Old Testament.

Although it may seem strange that poetic books

such as Job or Proverbs

would be included in the “prophets” category,

it was common for the Jews to see any writer of Scripture

as a prophet. Further,

many of the psalms are clear

messianic prophecies.

When Philip invited his friend Nathanael to meet Jesus, he referred to the whole of Hebrew Scripture in its two-fold division:

“We have found

the one Moses wrote about in the law,

and the prophets also

wrote about—Jesus of Nazareth”

(John 1:45, NET).

Philip was right that all of Scripture

has a common theme:

the Messiah,

the Son of God,

who is Jesus.

The phrase the law and the prophets

https://youtu.be/wF0KYWKXZ0s

refers to the entire Hebrew Bible, what we call the Old Testament.

Jesus spoke of

“the law and the prophets”

multiple times,

such as when He listed the two greatest commandments

(Matthew 22:40).

In the

Sermon on the Mount,

Jesus pointed to His absolute perfection,

saying,

“Do not think that I have come to abolish

the

Law or the Prophets;

I have not come to abolish them

but to fulfill them”

(Matthew 5:17).

On the Emmaus Road,

Jesus taught two disciples

“everything written about himself

in the Scriptures,

beginning

with the

Law of Moses

and the

Books of the Prophets”

(Luke 24:27, CEV).

Clearly, all Scripture, indicated by “the law and the prophets,”

pointed to Jesus.

The same passage also contains a three-fold division of the Old Testament:

“the Law of Moses,

the Prophets and

the

Psalms”

(verse 44),

but the two-fold division of “the law and the prophets”

was also customary (Matthew 7:12; Acts 13:15; 24:14; Romans 3:21).

The books of the law, properly speaking, would comprise the Pentateuch: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

The prophets, in the two-fold division, would include

the rest of the Old Testament.

Although it may seem strange that poetic books

such as Job or Proverbs

would be included in the “prophets” category,

it was common for the Jews to see any writer of Scripture

as a prophet. Further,

many of the psalms are clear

messianic prophecies.

When Philip invited his friend Nathanael to meet Jesus, he referred to the whole of Hebrew Scripture in its two-fold division:

“We have found

the one Moses wrote about in the law,

and the prophets also

wrote about—Jesus of Nazareth”

(John 1:45, NET).

Philip was right that all of Scripture

has a common theme:

the Messiah,

the Son of God,

who is Jesus.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed