Christ uses the Parable of the Ten Minas

in Luke 19:11–27

to teach

about the coming kingdom of God

on

earth

The occasion of the parable is Jesus’ final trip to Jerusalem. Many people in the crowd along the road believed that He was going to Jerusalem in order to establish His earthly kingdom immediately. (Of course, He was going to Jerusalem in order to die, as He had stated in Luke 18:33.) Jesus used this parable to dispel any hopeful rumors that the time of the kingdom had arrived.

In the parable, a nobleman leaves for a foreign country in order to be made king. Before he left, he gave ten minas to ten of his servants (Luke 19:12–13). A mina was a good sum of money (about three months’ wages), and the future king said, “Put this money to work . . . until I come back” (verse 13).

However, the man’s subjects “hated him” and sent word to him that they refused to acknowledge his kingship (Luke 19:14). When the man was crowned king, he returned to his homeland and began to set things right. First, he called the ten servants to whom he had loaned the minas. They each gave an account for how they had used the money. The first servant showed that his mina had earned ten more. The king was pleased, saying, “‘Well done, good and faithful servant! . . . Because you have been trustworthy in a very small matter, take charge of ten cities” (verse 17). The next servant’s investment had yielded five additional minas, and that servant was rewarded with charge of five cities (verses 18–19).

Then came a servant who reported that he had done nothing with his mina except hide it in a cloth (Luke 19:20). His reason: “I was afraid of you, because you are a hard man. You take out what you did not put in and reap what you did not sow” (verse 21). The king responded to the servant’s description of him as “hard” by showing hardness, calling him a “wicked servant” and commanding for his mina to be given to the one who had earned ten (verses 22 and 24). Some bystanders said, “Sir . . . he already has ten!” and the king replied, “I tell you that to everyone who has, more will be given, but as for the one who has nothing, even what they have will be taken away”

(verses 25–26).

Finally, the king commanded that his enemies—those who had rebelled against his authority—be brought before him.

Right there in the king’s presence, they were executed (Luke 19:27).

In this parable, Jesus teaches several things about

the Millennial Kingdom and the time leading up to it.

As Luke 19:11 indicates,

Jesus’ most basic point

is that the kingdom was not going to appear immediately.

There would be a period of time,

during which the king would be absent,

before the kingdom would be set up.

The nobleman in the

parable is Jesus,

who left this world

but

who will return as King some day.

The servants the king charges with a task represent followers of Jesus.

The Lord has given us a

valuable commission,

and

we must be faithful to

serve Him until He returns.

Upon His return,

Jesus will ascertain the faithfulness of His own people

(see Romans 14:10–12).

There is work to be done

(John 9:4),

and we must use what God has given us for

His glory.

There are promised rewards for those who

are

faithful in their charge.

The enemies who rejected the king

in the parable are representative of the

Jewish nation

that rejected Christ while He walked on earth--

and everyone

who still denies Him today.

When Jesus returns to establish His kingdom,

one of the

first things He will do is utterly defeat His enemies

(Revelation 19:11–15).

It does not pay to fight

against the

King of kings.

The Parable of the Ten Minas is similar to the

Parable of the Talents in Matthew 25:14–30.

Some people assume that they are

the same parable,

but there are enough differences to

warrant a distinction:

the

parable of the minas

was told

on the

road between Jericho and Jerusalem;

the parable of the talents was

told later

on the Mount of Olives.

The audience for the parable of the minas

was

a large crowd;

the audience for

the

parable of the talents was

the

disciples by themselves.

The parable of the minas deals with two classes of people:

servants and enemies;

the parable of the talents deals only with professed servants.

In the parable of the minas, each servant receives the same amount;

in the parable of the talents, each servant receives a different amount

(and talents are worth far more than minas).

Also, the return is different:

in the parable of the minas,

the servants report ten-fold and five-fold earnings;

in the parable of the talents,

all the good servants double their investment.

In the former, the servants received identical gifts; in the latter,

the

good servants showed identical faithfulness.

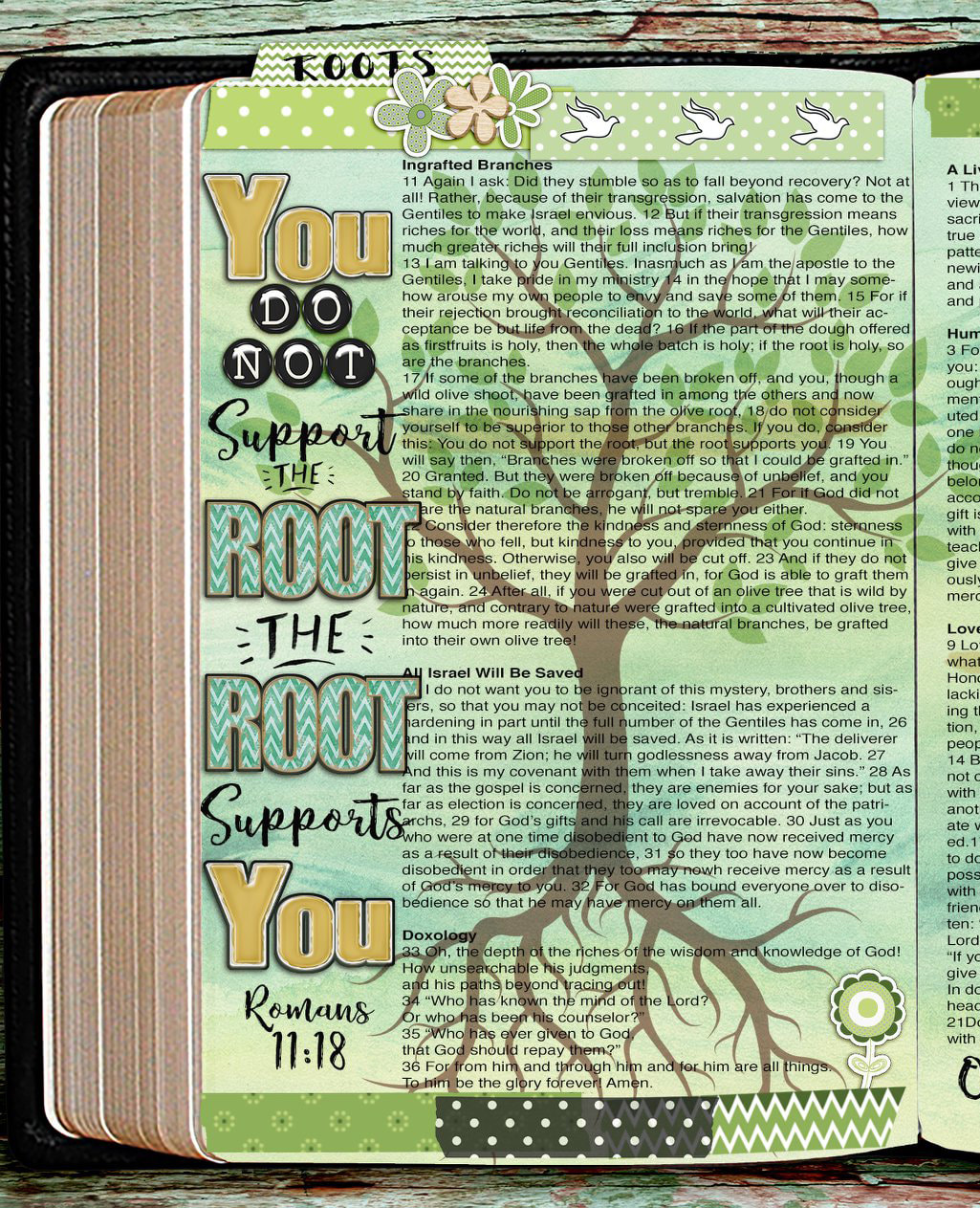

Members of the church in Rome

were united in their faith in Jesus Christ,

but the apostle Paul recognized a division

between the Jewish and Gentile believers

among them.

The two groups of Christians were arguing and

passing judgment on one another, and Paul

told them to stop

"quarreling over disputable matters”

(Romans 14:1).

The entire chapter of Romans 14 deals with the question of disputable matters.

Disputable matters can be summed up as

non-essential issues

in the Christian life,

or “gray areas” in which the Bible does not spell out clear guidelines.

While many things in the Christian life

are essential,

some are not.

The two specific disputable matters that Paul addressed in Romans 14

were chiefly regarding which foods were acceptable to eat (verses 2–3)

and the observance of certain holy days (verses 5–6).

He also touched on drinking wine in verse 21.

The Roman Christians had become partisan.

Love and unity

were being forgotten

amid their disputes.

Some of the believers in the church felt freedom in Christ to eat all kinds of foods without restriction. It is unclear whether these restrictions dealt only with kosher regulations as spelled out in the Jewish law, or also included eating meat that had been offered to pagan idols. Those who were weak in faith may have felt too much temptation when eating meat and thus gave up anything that reminded them of their pre-Christian life.

Likewise,

some Christians who had always worshiped God

on the required Jewish holy days

may have

felt hollow and faithless

if

they didn’t continue

to dedicate those days to God.

The problem was that the “strong” Christians

were looking down on the weaker ones,

and the “weak” believers

were condemning or judging

the strong.

How might this cause a Christian of weaker faith to sin?

Paul has said clearly that for anyone who believes

a specific food or drink to be unclean,

that thing really is unclean

for that person.

In other words, if they choose to follow the example of another

believer who eats or drinks freely, they might sin

by violating their own conscience.

Paul's bottom-line to those stronger-faith Christians is clear:

Don't do what is wrong. Instead, do what is good.

Even if it means "giving up" your freedom voluntarily for a specific time or purpose. Even if that means eating only vegetables, today,

for the sake of those of weaker faith.

If it shows love to a "weak in faith" fellow believer, it's worth that.

The church was caught

up in the

sins of

pride, legalism,

and

judgmentalism

Paul reminded them that,

as

servants of God,

they were

accountable to God alone:

"Who are you

to pass judgment on

the

servant of another?

It is before his own master that

he stands or falls.

And he will be upheld,

for

the Lord is able

to

make him stand”

(Romans 14:4, ESV).

God is our Master, and it’s up

to Him to judge us.

If we are busy serving our Master,

we

won’t be concerned with

trivial matters

like

investigating

the eating habits of

our brothers and sisters.

The overarching lesson of the chapter is that

harmonious relationships

in the body of Christ

are critical to God.

Unity in the church is more important than

agreement on debatable,

less significant matters

in

the Christian life.

Disputable matters should

not disrupt

Christian oneness

God calls Christians to

live

without judging each other

and

without causing others

to

violate their consciences:

"Therefore let us

stop passing judgment on one another.

Instead, make up your mind

not to put any stumbling block

or

obstacle in the way of a brother or sister”

(Romans 14:13).

Mature Christians who

have freedom in Christ in a certain area

should be careful not to influence weaker brothers and sisters

to stumble and

violate their conscience.

Even if -we believe- we are right,

if -our actions- will cause another believer

to -falter spiritually-

we are to stop what we are doing.

And weak or less mature believers who have

strong convictions

in an area must avoid

restricting or judging those who

have

discovered Christian freedom

Mutual respect and love

are the marks of

true Christian disciples

(John 13:34–35).

Paul said,

“Accept the one whose faith is weak”

(Romans 14:1).

He meant that the strong should consider the

weak as fellow believers and equals in

the body of Christ.

The lesson of Romans 14 still speaks forcefully today.

If Christians disagree on

non-essential, disputable matters,

neither side

should

condemn or judge the other,

but both should be allowed

to worship God as they are

“fully convinced

in

their own mind”

(verse 5).

Paul stressed a

critical concern in God’s kingdom--

that brothers and sisters act in love

(Romans 14:15).

Christians won’t be known for what they eat or drink,

but for their love, righteousness, peace, and joy

in the

Holy Spirit

(verse 17).

Paul longed to see the believers in Rome

living sacrificially

and

agreeing to disagree

despite their differences.

In this way, the

church could turn its focus away

from

insignificant matters

onto the

great commission

of

spreading the

gospel of Jesus Christ

to the world.

After the Tribulation and the Battle of Armageddon,

Jesus will establish His 1,000-year Kingdom on earth. In Jeremiah 30,

God promises Israel that the yoke of foreign oppression would be cast off forever, and “instead, they will serve the Lord their God and David their king, whom I will raise up for them” (verse 9).

Speaking of the same time, God says through the prophet Ezekiel,

“My servant David will be king over them,

and they will all have one shepherd.

They will follow my laws and be careful to keep my decrees”

(Ezekiel 37:24).

From the prophecies of Jeremiah and Ezekiel, some have concluded that King David will be resurrected during the Millennium and installed

as co-regent over Israel, ruling the Kingdom with

Jesus Christ.

Jeremiah’s and Ezekiel’s prophecies should be understood this way:

the Jews would one day return to their own country,

their yoke of slavery would be removed,

their fellowship with God would be restored, and God would provide them with a King of His own choosing.

This King would, in some way, be like King David of old.

These passages can refer to none

other than the long-awaited

Messiah,

the “Servant of the Lord” (cf. Isaiah 42:1).

The Jews sometimes referred to the Messiah as “David”

because it was known the Messiah would come from David’s lineage.

The New Testament often refers to

Jesus as the “Son of David” (Matthew 15:22; Mark 10:47).

There are other reasons,

besides being the Son of David,

that the

Messiah is referred to as “David.”

King David in the Old Testament

was a man after God’s own heart

(Acts 13:22),

he was an unlikely king of God’s own choosing,

and the

Spirit of God was upon Him

(1 Samuel 16:12–13).

David, then, is a type of Christ

(a type is a person who foreshadows someone else).

Another example of this kind of typology is Elijah,

whose ministry foreshadowed that of John the Baptist

to the extent that Malachi called John “Elijah”

(Malachi 4:5; cf. Luke 1:17; Mark 9:11–13).

David will be resurrected

at the beginning of the Millennium,

along with all the other Old Testament saints.

And David will be one of those who

reign with Jesus in the Kingdom

(Daniel 7:27).

However, all believers will rule the nations (Revelation 2:26–27; 20:4) and judge the world (1 Corinthians 6:2). The apostle Peter calls Christians “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation” (1 Peter 2:9). In Revelation 3:21,

Jesus says about the believer

who conquers,

“I will grant him to sit with me on my throne.” In some sense,

then, Christians will share authority with Christ

(cf. Ephesians 2:6).

There is some biblical evidence, as in the Parable of the Ten Minas (Luke 19:11–27),

that individuals will be given more or less authority

in the Kingdom according to

how they handle

the responsibilities

God has given them

in this age

(Luke 19:17).

Jesus

is the

King of kings

(Revelation 19:16).

Humanly speaking, Jesus is from the Davidic dynasty;

but in

power, in glory, in righteousness,

and in

every other way,

He is rightly called the Greater David.

“The government will be on his shoulders”

(Isaiah 9:6).

The Old and New Testaments

reveal that

the

future King during the Millennium

and all eternity is Jesus Christ

and

Him alone

(Jeremiah 23:5; Isaiah 9:7; 33:22; Revelation 17:14; 1 Timothy 6:15).

in Luke 19:11–27

to teach

about the coming kingdom of God

on

earth

The occasion of the parable is Jesus’ final trip to Jerusalem. Many people in the crowd along the road believed that He was going to Jerusalem in order to establish His earthly kingdom immediately. (Of course, He was going to Jerusalem in order to die, as He had stated in Luke 18:33.) Jesus used this parable to dispel any hopeful rumors that the time of the kingdom had arrived.

In the parable, a nobleman leaves for a foreign country in order to be made king. Before he left, he gave ten minas to ten of his servants (Luke 19:12–13). A mina was a good sum of money (about three months’ wages), and the future king said, “Put this money to work . . . until I come back” (verse 13).

However, the man’s subjects “hated him” and sent word to him that they refused to acknowledge his kingship (Luke 19:14). When the man was crowned king, he returned to his homeland and began to set things right. First, he called the ten servants to whom he had loaned the minas. They each gave an account for how they had used the money. The first servant showed that his mina had earned ten more. The king was pleased, saying, “‘Well done, good and faithful servant! . . . Because you have been trustworthy in a very small matter, take charge of ten cities” (verse 17). The next servant’s investment had yielded five additional minas, and that servant was rewarded with charge of five cities (verses 18–19).

Then came a servant who reported that he had done nothing with his mina except hide it in a cloth (Luke 19:20). His reason: “I was afraid of you, because you are a hard man. You take out what you did not put in and reap what you did not sow” (verse 21). The king responded to the servant’s description of him as “hard” by showing hardness, calling him a “wicked servant” and commanding for his mina to be given to the one who had earned ten (verses 22 and 24). Some bystanders said, “Sir . . . he already has ten!” and the king replied, “I tell you that to everyone who has, more will be given, but as for the one who has nothing, even what they have will be taken away”

(verses 25–26).

Finally, the king commanded that his enemies—those who had rebelled against his authority—be brought before him.

Right there in the king’s presence, they were executed (Luke 19:27).

In this parable, Jesus teaches several things about

the Millennial Kingdom and the time leading up to it.

As Luke 19:11 indicates,

Jesus’ most basic point

is that the kingdom was not going to appear immediately.

There would be a period of time,

during which the king would be absent,

before the kingdom would be set up.

The nobleman in the

parable is Jesus,

who left this world

but

who will return as King some day.

The servants the king charges with a task represent followers of Jesus.

The Lord has given us a

valuable commission,

and

we must be faithful to

serve Him until He returns.

Upon His return,

Jesus will ascertain the faithfulness of His own people

(see Romans 14:10–12).

There is work to be done

(John 9:4),

and we must use what God has given us for

His glory.

There are promised rewards for those who

are

faithful in their charge.

The enemies who rejected the king

in the parable are representative of the

Jewish nation

that rejected Christ while He walked on earth--

and everyone

who still denies Him today.

When Jesus returns to establish His kingdom,

one of the

first things He will do is utterly defeat His enemies

(Revelation 19:11–15).

It does not pay to fight

against the

King of kings.

The Parable of the Ten Minas is similar to the

Parable of the Talents in Matthew 25:14–30.

Some people assume that they are

the same parable,

but there are enough differences to

warrant a distinction:

the

parable of the minas

was told

on the

road between Jericho and Jerusalem;

the parable of the talents was

told later

on the Mount of Olives.

The audience for the parable of the minas

was

a large crowd;

the audience for

the

parable of the talents was

the

disciples by themselves.

The parable of the minas deals with two classes of people:

servants and enemies;

the parable of the talents deals only with professed servants.

In the parable of the minas, each servant receives the same amount;

in the parable of the talents, each servant receives a different amount

(and talents are worth far more than minas).

Also, the return is different:

in the parable of the minas,

the servants report ten-fold and five-fold earnings;

in the parable of the talents,

all the good servants double their investment.

In the former, the servants received identical gifts; in the latter,

the

good servants showed identical faithfulness.

Members of the church in Rome

were united in their faith in Jesus Christ,

but the apostle Paul recognized a division

between the Jewish and Gentile believers

among them.

The two groups of Christians were arguing and

passing judgment on one another, and Paul

told them to stop

"quarreling over disputable matters”

(Romans 14:1).

The entire chapter of Romans 14 deals with the question of disputable matters.

Disputable matters can be summed up as

non-essential issues

in the Christian life,

or “gray areas” in which the Bible does not spell out clear guidelines.

While many things in the Christian life

are essential,

some are not.

The two specific disputable matters that Paul addressed in Romans 14

were chiefly regarding which foods were acceptable to eat (verses 2–3)

and the observance of certain holy days (verses 5–6).

He also touched on drinking wine in verse 21.

The Roman Christians had become partisan.

Love and unity

were being forgotten

amid their disputes.

Some of the believers in the church felt freedom in Christ to eat all kinds of foods without restriction. It is unclear whether these restrictions dealt only with kosher regulations as spelled out in the Jewish law, or also included eating meat that had been offered to pagan idols. Those who were weak in faith may have felt too much temptation when eating meat and thus gave up anything that reminded them of their pre-Christian life.

Likewise,

some Christians who had always worshiped God

on the required Jewish holy days

may have

felt hollow and faithless

if

they didn’t continue

to dedicate those days to God.

The problem was that the “strong” Christians

were looking down on the weaker ones,

and the “weak” believers

were condemning or judging

the strong.

How might this cause a Christian of weaker faith to sin?

Paul has said clearly that for anyone who believes

a specific food or drink to be unclean,

that thing really is unclean

for that person.

In other words, if they choose to follow the example of another

believer who eats or drinks freely, they might sin

by violating their own conscience.

Paul's bottom-line to those stronger-faith Christians is clear:

Don't do what is wrong. Instead, do what is good.

Even if it means "giving up" your freedom voluntarily for a specific time or purpose. Even if that means eating only vegetables, today,

for the sake of those of weaker faith.

If it shows love to a "weak in faith" fellow believer, it's worth that.

The church was caught

up in the

sins of

pride, legalism,

and

judgmentalism

Paul reminded them that,

as

servants of God,

they were

accountable to God alone:

"Who are you

to pass judgment on

the

servant of another?

It is before his own master that

he stands or falls.

And he will be upheld,

for

the Lord is able

to

make him stand”

(Romans 14:4, ESV).

God is our Master, and it’s up

to Him to judge us.

If we are busy serving our Master,

we

won’t be concerned with

trivial matters

like

investigating

the eating habits of

our brothers and sisters.

The overarching lesson of the chapter is that

harmonious relationships

in the body of Christ

are critical to God.

Unity in the church is more important than

agreement on debatable,

less significant matters

in

the Christian life.

Disputable matters should

not disrupt

Christian oneness

God calls Christians to

live

without judging each other

and

without causing others

to

violate their consciences:

"Therefore let us

stop passing judgment on one another.

Instead, make up your mind

not to put any stumbling block

or

obstacle in the way of a brother or sister”

(Romans 14:13).

Mature Christians who

have freedom in Christ in a certain area

should be careful not to influence weaker brothers and sisters

to stumble and

violate their conscience.

Even if -we believe- we are right,

if -our actions- will cause another believer

to -falter spiritually-

we are to stop what we are doing.

And weak or less mature believers who have

strong convictions

in an area must avoid

restricting or judging those who

have

discovered Christian freedom

Mutual respect and love

are the marks of

true Christian disciples

(John 13:34–35).

Paul said,

“Accept the one whose faith is weak”

(Romans 14:1).

He meant that the strong should consider the

weak as fellow believers and equals in

the body of Christ.

The lesson of Romans 14 still speaks forcefully today.

If Christians disagree on

non-essential, disputable matters,

neither side

should

condemn or judge the other,

but both should be allowed

to worship God as they are

“fully convinced

in

their own mind”

(verse 5).

Paul stressed a

critical concern in God’s kingdom--

that brothers and sisters act in love

(Romans 14:15).

Christians won’t be known for what they eat or drink,

but for their love, righteousness, peace, and joy

in the

Holy Spirit

(verse 17).

Paul longed to see the believers in Rome

living sacrificially

and

agreeing to disagree

despite their differences.

In this way, the

church could turn its focus away

from

insignificant matters

onto the

great commission

of

spreading the

gospel of Jesus Christ

to the world.

After the Tribulation and the Battle of Armageddon,

Jesus will establish His 1,000-year Kingdom on earth. In Jeremiah 30,

God promises Israel that the yoke of foreign oppression would be cast off forever, and “instead, they will serve the Lord their God and David their king, whom I will raise up for them” (verse 9).

Speaking of the same time, God says through the prophet Ezekiel,

“My servant David will be king over them,

and they will all have one shepherd.

They will follow my laws and be careful to keep my decrees”

(Ezekiel 37:24).

From the prophecies of Jeremiah and Ezekiel, some have concluded that King David will be resurrected during the Millennium and installed

as co-regent over Israel, ruling the Kingdom with

Jesus Christ.

Jeremiah’s and Ezekiel’s prophecies should be understood this way:

the Jews would one day return to their own country,

their yoke of slavery would be removed,

their fellowship with God would be restored, and God would provide them with a King of His own choosing.

This King would, in some way, be like King David of old.

These passages can refer to none

other than the long-awaited

Messiah,

the “Servant of the Lord” (cf. Isaiah 42:1).

The Jews sometimes referred to the Messiah as “David”

because it was known the Messiah would come from David’s lineage.

The New Testament often refers to

Jesus as the “Son of David” (Matthew 15:22; Mark 10:47).

There are other reasons,

besides being the Son of David,

that the

Messiah is referred to as “David.”

King David in the Old Testament

was a man after God’s own heart

(Acts 13:22),

he was an unlikely king of God’s own choosing,

and the

Spirit of God was upon Him

(1 Samuel 16:12–13).

David, then, is a type of Christ

(a type is a person who foreshadows someone else).

Another example of this kind of typology is Elijah,

whose ministry foreshadowed that of John the Baptist

to the extent that Malachi called John “Elijah”

(Malachi 4:5; cf. Luke 1:17; Mark 9:11–13).

David will be resurrected

at the beginning of the Millennium,

along with all the other Old Testament saints.

And David will be one of those who

reign with Jesus in the Kingdom

(Daniel 7:27).

However, all believers will rule the nations (Revelation 2:26–27; 20:4) and judge the world (1 Corinthians 6:2). The apostle Peter calls Christians “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation” (1 Peter 2:9). In Revelation 3:21,

Jesus says about the believer

who conquers,

“I will grant him to sit with me on my throne.” In some sense,

then, Christians will share authority with Christ

(cf. Ephesians 2:6).

There is some biblical evidence, as in the Parable of the Ten Minas (Luke 19:11–27),

that individuals will be given more or less authority

in the Kingdom according to

how they handle

the responsibilities

God has given them

in this age

(Luke 19:17).

Jesus

is the

King of kings

(Revelation 19:16).

Humanly speaking, Jesus is from the Davidic dynasty;

but in

power, in glory, in righteousness,

and in

every other way,

He is rightly called the Greater David.

“The government will be on his shoulders”

(Isaiah 9:6).

The Old and New Testaments

reveal that

the

future King during the Millennium

and all eternity is Jesus Christ

and

Him alone

(Jeremiah 23:5; Isaiah 9:7; 33:22; Revelation 17:14; 1 Timothy 6:15).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed